(Rhynchocephalia)

Rhynchocephalians

Дзьобоголові

(Sphenodon punctatus)

Tuatara

Гатерія

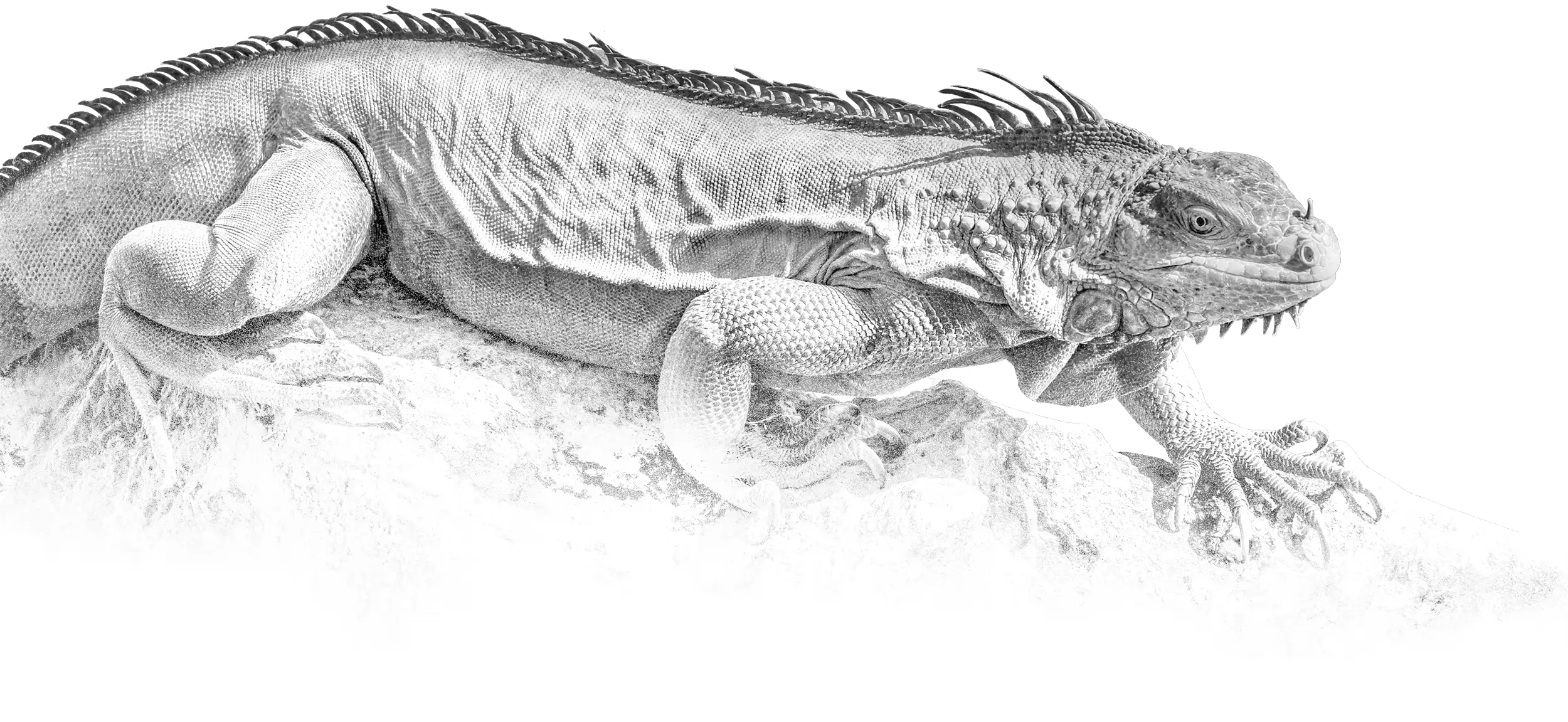

Rhynchocephalia is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose group with high morphological and ecological diversity. The oldest record of the group is dated to the Middle Triassic around 244 million years ago, and they had achieved global distribution by the Early Jurassic.

While there is currently considered to be only one living species of tuatara, two species were previously identified: Sphenodon punctatus, or northern tuatara, and the much rarer Sphenodon guntheri, or Brothers Island tuatara, which is confined to North Brother Island in Cook Strait. A 2009 paper re-examined the genetic bases used to distinguish the two supposed species of tuatara, and concluded they represent only geographic variants, and only one species should be recognised. Consequently, the northern tuatara was re-classified as Sphenodon punctatus punctatus and the Brothers Island tuatara as Sphenodon punctatus guntheri. The Brothers Island tuatara has olive brown skin with yellowish patches, while the colour of the northern tuatara ranges from olive green through grey to dark pink or brick red, often mottled, and always with white spots. In addition, the Brothers Island tuatara is considerably smaller.

Distribution and threats

Tuatara were once widespread on New Zealand’s main North and South Islands, where subfossil remains have been found in sand dunes, caves, and Māori middens. Wiped out from the main islands before European settlement, they were long confined to 32 offshore islands free of mammals. The islands are difficult to get to, and are colonised by few animal species, indicating that some animals absent from these islands may have caused tuatara to disappear from the mainland. However, kiore (Polynesian rats) had recently become established on several of the islands, and tuatara were persisting, but not breeding, on these islands. Additionally, tuatara were much rarer on the rat-inhabited islands. Prior to conservation work, 25% of the distinct tuatara populations had become extinct in the past century.

The recent discovery of a tuatara hatchling on the mainland indicates that attempts to re-establish a breeding population on the New Zealand mainland have had some success. The total population of tuatara is estimated to be between 60,000 and 100,000.

Eyes

The eyes can focus independently, and are specialised with three types of photoreceptive cells, all with fine structural characteristics of retinal cone cells used for both day and night vision, and a tapetum lucidum which reflects onto the retina to enhance vision in the dark. There is also a third eyelid on each eye, the nictitating membrane. Five visual opsin genes are present, suggesting good colour vision, possibly even at low light levels.

Parietal eye

Like some other living vertebrates, including some lizards, the tuatara has a third eye on the top of its head called the parietal eye (also called a pineal or third eye) formed by the parapineal organ, with an accompanying opening in the skull roof called the pineal or parietal foramen, enclosed by the parietal bones. It has its own lens, a parietal plug which resembles a cornea, retina with rod-like structures, and degenerated nerve connection to the brain. The parietal eye is visible only in hatchlings, which have a translucent patch at the top centre of the skull. After four to six months, it becomes covered with opaque scales and pigment. While capable of detecting light, it is probably not capable of detecting movement or forming an image. It likely serves to regulate the circadian rhythm and possibly detect seasonal changes, and help with thermoregulation.

Hearing

Together with turtles, the tuatara has the most primitive hearing organs among the amniotes. There is no tympanum (eardrum) and no earhole, and the middle ear cavity is filled with loose tissue, mostly adipose tissue (fat). The stapes comes into contact with the quadrate (which is immovable), as well as the hyoid and squamosal. The hair cells are unspecialised, innervated by both afferent and efferent nerve fibres, and respond only to low frequencies. Though the hearing organs are poorly developed and primitive with no visible external ears, they can still show a frequency response from 100 to 800 Hz, with peak sensitivity of 40 dB at 200 Hz.

Odorant receptors

Animals that depend on the sense of smell to capture prey, escape from predators or simply interact with the environment they inhabit, usually have many odorant receptors. These receptors are expressed in the dendritic membranes of the neurons for the detection of odours. The tuatara has around 472 receptors, a number more similar to what birds have than to the large number of receptors that turtles and crocodiles may have.

Spine and ribs

The tuatara spine is made up of hourglass-shaped amphicoelous vertebrae, concave both before and behind. This is the usual condition of fish vertebrae and some amphibians, but is unique to tuatara within the amniotes. The vertebral bodies have a tiny hole through which a constricted remnant of the notochord passes; this was typical in early fossil reptiles, but lost in most other amniotes.

The tuatara has gastralia, rib-like bones also called gastric or abdominal ribs, the presumed ancestral trait of diapsids. They are found in some lizards, where they are mostly made of cartilage, as well as crocodiles and the tuatara, and are not attached to the spine or thoracic ribs. The true ribs are small projections, with small, hooked bones, called uncinate processes, found on the rear of each rib. This feature is also present in birds. The tuatara is the only living tetrapod with well-developed gastralia and uncinate processes.

In the early tetrapods, the gastralia and ribs with uncinate processes, together with bony elements such as bony plates in the skin (osteoderms) and clavicles (collar bone), would have formed a sort of exoskeleton around the body, protecting the belly and helping to hold in the guts and inner organs. These anatomical details most likely evolved from structures involved in locomotion even before the vertebrates ventured onto land. The gastralia may have been involved in the breathing process in early amphibians and reptiles. The pelvis and shoulder girdles are arranged differently from those of lizards, as is the case with other parts of the internal anatomy and its scales.

Tail and back

The spiny plates on the back and tail of the tuatara resemble those of a crocodile more than a lizard, but the tuatara shares with lizards the ability to break off its tail when caught by a predator, and then regenerate it. The regrowth takes a long time and differs from that of lizards. The cloacal glands of tuatara have a unique organic compound named tuataric acid.

Physiology

Adult tuatara are terrestrial and nocturnal reptiles, though they will often bask in the sun to warm their bodies. Hatchlings hide under logs and stones, and are diurnal, likely because adults are cannibalistic. Juveniles are typically active at night, but can be found active during the day. The juveniles’ movement pattern is attributed to genetic hardwire of conspecifics for predator avoidance and thermal restrictions. Tuatara thrive in temperatures much lower than those tolerated by most reptiles, and hibernate during winter. They remain active at temperatures as low as 5 °C, while temperatures over 28 °C are generally fatal. The optimal body temperature for the tuatara is from 16 to 21 °C, the lowest of any reptile. The body temperature of tuatara is lower than that of other reptiles, ranging from 5.2–11.2 °C over a day, whereas most reptiles have body temperatures around 20 °C. The low body temperature results in a slower metabolism.

Ecology

Burrowing seabirds such as petrels, prions, and shearwaters share the tuatara’s island habitat during the birds’ nesting seasons. The tuatara use the birds’ burrows for shelter when available, or dig their own. The seabirds’ guano helps to maintain invertebrate populations on which tuatara predominantly prey, including beetles, crickets, spiders, wētās, earthworms, and snails. Their diets also consist of frogs, lizards, and bird’s eggs and chicks. Young tuatara are also occasionally cannibalised. The diet of the tuatara varies seasonally, and they consume mainly fairy prions and their eggs in the summer. In total darkness no feeding attempt was observed, and the lowest light intensity at which an attempt to snatch a beetle was observed occurred under 0.0125 lux. The eggs and young of seabirds that are seasonally available as food for tuatara may provide beneficial fatty acids. Tuatara of both sexes defend territories, and will threaten and eventually bite intruders. The bite can cause serious injury. Tuatara will bite when approached, and will not let go easily. Female tuatara rarely exhibit parental behaviour by guarding nests on islands with high rodent populations.

Tuataras are parasitised by the tuatara tick (Archaeocroton sphenodonti), a tick that directly depends on tuataras. These ticks tend to be more prevalent on larger males, as they have larger home ranges than smaller and female tuatara and interact with other tuatara more in territorial displays.

Reproduction

Tuatara reproduce very slowly, taking 10 to 20 years to reach sexual maturity. Though their reproduction rate is slow, tuatara have the fastest swimming sperm by two to four times compared to all reptiles studied earlier. Mating occurs in midsummer; females mate and lay eggs once every four years. During courtship, a male makes his skin darker, raises his crests, and parades toward the female. He slowly walks in circles around the female with stiffened legs. The female will either allow the male to mount her, or retreat to her burrow. Males do not have a penis; they have rudimentary hemipenes; meaning that intromittent organs are used to deliver sperm to the female during copulation. They reproduce by the male lifting the tail of the female and placing his vent over hers. This process is sometimes referred to as a “cloacal kiss”. The sperm is then transferred into the female, much like the mating process in birds. Along with birds, the tuatara is one of the few members of Amniota to have lost the ancestral penis.

Tuatara eggs have a soft, parchment-like 0.2 mm thick shell that consists of calcite crystals embedded in a matrix of fibrous layers. It takes the females between one and three years to provide eggs with yolk, and up to seven months to form the shell. It then takes between 12 and 15 months from copulation to hatching. This means reproduction occurs at two- to five-year intervals, the slowest in any reptile. Survival of embryos has also been linked to having more success in moist conditions. Wild tuatara are known to be still reproducing at about 60 years of age; “Henry”, a male tuatara at Southland Museum in Invercargill, New Zealand, became a father (possibly for the first time) on 23 January 2009, at age 111, with an 80 year-old female.

The sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature of the egg, with warmer eggs tending to produce male tuatara, and cooler eggs producing females. Eggs incubated at 21 °C have an equal chance of being male or female. However, at 22 °C, 80% are likely to be males, and at 20 °C, 80% are likely to be females; at 18 °C all hatchlings will be females. Some evidence indicates sex determination in tuatara is determined by both genetic and environmental factors.

Tuatara probably have the slowest growth rates of any reptile, continuing to grow larger for the first 35 years of their lives. The average lifespan is about 60 years, but they can live to be well over 100 years old; tuatara could be the reptile with the second longest lifespan after tortoises. Some experts believe that captive tuatara could live as long as 200 years. This may be related to genes that offer protection against reactive oxygen species.