(Crocodylia)

Crocodilians

Крокодилоподібні

Crocodilia is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. The order includes the true crocodiles (family Crocodylidae), the alligators and caimans (family Alligatoridae), and the gharial and false gharial (family Gavialidae).

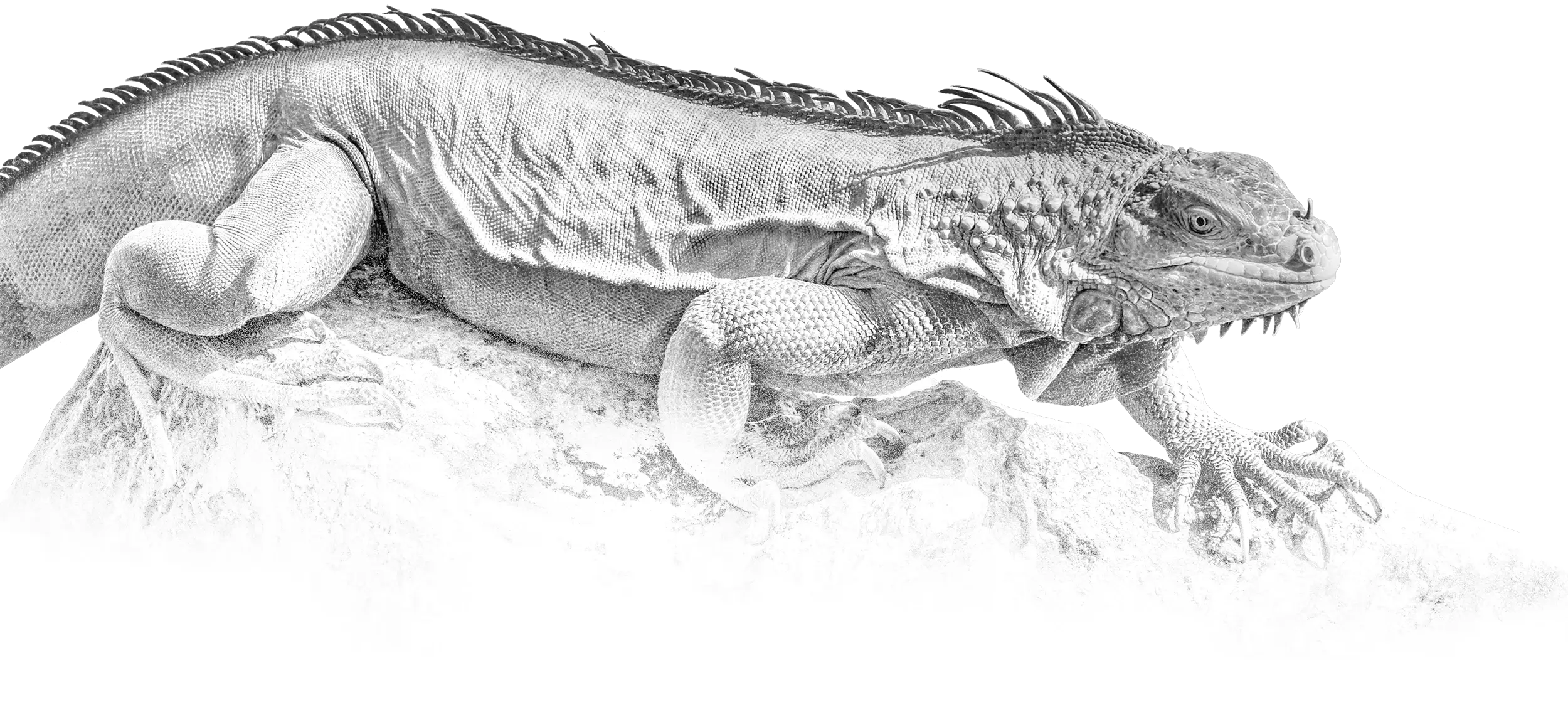

Extant crocodilians have flat heads with long snouts and tails that are compressed on the sides, with their eyes, ears, and nostrils at the top of the head. Alligators and caimans tend to have broader U-shaped jaws that, when closed, show only the upper teeth, whereas crocodiles usually have narrower V-shaped jaws with both rows of teeth visible when closed. Gharials have extremely slender, elongated jaws. The teeth are conical and peg-like, and the bite is powerful. All crocodilians are good swimmers and can move on land in a “high walk” position, traveling with their legs erect rather than sprawling. Crocodilians have thick skin covered in non-overlapping scales and, like birds, crocodilians have a four-chambered heart and lungs with unidirectional airflow.

Like most other reptiles, crocodilians are ectotherms or ‘cold-blooded’. They are found mainly in the warm and tropical areas of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, usually occupying freshwater habitats, though some can live in saline environments and even swim out to sea. Crocodilians have a largely carnivorous diet; some species like the gharial are specialized feeders while others, like the saltwater crocodile, have generalized diets. They are generally solitary and territorial, though they sometimes hunt in groups. During the breeding season, dominant males try to monopolize available females, which lay their eggs in holes or mounds and, like many birds, they care for their hatched young.

Though there is diversity in snout and tooth shape, all crocodilian species have essentially the same body morphology. They have solidly built, lizard-like bodies with wide, cylindrical torsos, flat heads, long snouts, short necks, and tails that are compressed from side to side. Their limbs are reduced in size; the front feet have five mostly non-webbed digits, and the hind feet have four webbed digits and an extra fifth. The pelvis and ribs of crocodilians are modified; the cartilaginous processes of the ribs allow the thorax to collapse when submerging and the structure of the pelvis can accommodate large amounts of food, or more air in the lungs. Both sexes have a cloaca, a single chamber and outlet near the tail into which the intestinal, urinary and genital tracts open. It houses the penis in males and the clitoris in females. The crocodilian penis is permanently erect; it relies on cloacal muscles to protrude it, and elastic ligaments and a tendon to retract it. The gonads are located near the kidneys.

Crocodilians range in size from the dwarf caimans and African dwarf crocodiles, which reach 1–1.5 m, to the saltwater crocodile and Nile crocodile, which reach 6 m and weigh up to 1,000 kg. Some prehistoric species such as the late-Cretaceous Deinosuchus were even larger, at up to about 11 m and 3,450 kg. Crocodilians tend to be sexually dimorphic; males are much larger than females.

Locomotion

Crocodilians are excellent swimmers. During aquatic locomotion, the muscular tail undulates from side to side to drive the animal through the water while the limbs are held close to the body to reduce drag. When the animal needs to stop or change direction, the limbs are splayed out. Swimming is normally achieved with gentle sinuous movements of the tail, but the animals can move more quickly when pursuing or being pursued. Crocodilians are less well-adapted for moving on land, and are unusual among vertebrates in having two means of terrestrial locomotion: the “high walk” and the “low walk”. The ankle joints flex in a different way from those of other reptiles, a feature crocodilians share with some early archosaurs. One of the upper row of ankle bones, the talus bone, moves with the tibia and fibula, while the heel bone moves with the foot and is where the ankle joint is located. The result is the legs can be held almost vertically beneath the body when on land, and the foot swings during locomotion as the ankle rotates.

The limbs move much the same as those of other quadrupeds; the left forelimb moves first, followed by the right hindlimb, then right forelimb, and finally left hindlimb. The high walk of crocodilians, with the belly and most of the tail held off the ground and the limbs held directly under the bodies, resembles that of mammals and birds. The low walk is similar to the high walk, but the body is not raised, and is quite different from the sprawling walk of salamanders and lizards. Crocodilians can instantly change from one walk to the other; the high walk is the usual means of locomotion on land. The animal may immediately push up its body up use this form, or it may take one or two strides of low walk before raising the body. Unlike most other land vertebrates, when crocodilians increase their pace of travel, they increase the speed at which the lower half of each limb (rather than the whole leg) swings forward, so stride length increases while stride duration decreases.

Though they are typically slow on land, crocodilians can produce brief bursts of speed; some can run at 12 to 14 km/h for short distances. In some small species, such as the freshwater crocodile, running can progress to galloping, which involves the hind limbs launching the body forward and the fore limbs subsequently taking the weight. Next, the hind limbs swing forward as the spine flexes dorso-ventrally, and this sequence of movements is repeated. During terrestrial locomotion, a crocodilian can keep its back and tail straight because muscles attach the scales to the vertebrae. Whether on land or in water, crocodilians can jump or leap by pressing their tails and hind limbs against the substrate and launching themselves into the air. A fast entry into water from a muddy bank can be effected by plunging to the ground, twisting the body from side to side and splaying out the limbs.

Jaws and teeth

The snout shape of crocodilians varies between species. Alligators and caimans generally have wide, U-shaped snouts while those of crocodiles are typically narrower and V-shaped. The snouts of the gharials are extremely elongated. The muscles that close the jaws are larger and more powerful than the ones that open them, and a human can quite easily hold shut a crocodilian’s jaws, but prying open the jaws is extremely difficult. The powerful closing muscles attach at the middle of the lower jaw. The jaw hinge attaches behind the atlanto-occipital joint, giving the animal a wide gape. A folded membrane holds the tongue stationary.

Crocodilians have some of the strongest bite forces in the animal kingdom. In a study published in 2003, an American alligator’s bite force was measured at up to 2,125 lbf (9.45 kN) and in a 2012 study, a saltwater crocodile’s bite force was measured at 3,700 lbf (16 kN). This study found no correlation between bite force and snout shape, though the gharial’s extremely slender jaws are relatively weak and are built for quick jaw closure. The bite force of Deinosuchus may have measured 23,000 lbf (100 kN), even greater than that of theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus.

Crocodilian teeth vary from dull and rounded to sharp and pointed. Broad-snouted species have teeth that vary in size, while those of slender-snouted species are more consistent. In general, in crocodiles and gharials, both rows of teeth are visible when the jaws are closed because their teeth fit into grooves along the outside lining of the upper jaw. By contrast, the lower teeth of alligators and caimans normally fit into holes along the inside lining of the upper jaw, so they are hidden when the jaws are closed. Crocodilians are homodonts, meaning each of their teeth are of the same type; they do not have different tooth types, such as canines and molars. Crocodilians are polyphyodonts; they are able to replace each of their approximately 80 teeth up to 50 times in their 35-to-75-year lifespan. Crocodilians are the only non-mammalian vertebrates with tooth sockets. Next to each full-grown tooth is a small replacement tooth and an odontogenic stem cell in the dental lamina that can be activated when required. Tooth replacement slows and eventually stops as the animal ages.

Sense organs

The eyes, ears and nostrils of crocodilians are at the top of the head; this placement allows them to stalk their prey with most of their bodies underwater. When in bright light, the pupils of a crocodilian contract into narrow slits, whereas in darkness they become large circles, as is typical for animals that hunt at night. Crocodilians’ eyes have a tapetum lucidum that enhances vision in low light. When the animal completely submerges, the nictitating membranes cover its eyes. Glands on the nictitating membrane secrete a salty lubricant that keeps the eye clean. When a crocodilian leaves the water and dries off, this substance is visible as “tears”. While eyesight in air is fairly good, it is significantly weakened underwater. Crocodilians appear to have undergone a “nocturnal bottleneck” early in their history, during which their eyes lost traits like sclerotic rings, an annular pad of the lens and coloured cone oil droplets, giving them dichromatic vision (red-green colourblindness). Since then, some crocodilians appear to have re-evolved full-colour vision.

The ears are adapted for hearing both in air and underwater, and the eardrums are protected by flaps that can be opened or closed by muscles. Crocodilians have a wide hearing range, with sensitivity comparable to most birds and many mammals. Hearing in crocodilians does not degrade as the animal ages because they can regrow and replace hair cells. The well-developed trigeminal nerve allows them to detect vibrations in water, such as those made by potential prey. Crocodilians have a single olfactory chamber and the vomeronasal organ disappears when they reach adulthood. Behavioural and olfactometer experiments indicate crocodiles detect both air-borne and water-soluble chemicals, and use their olfactory system for hunting. When above water, crocodiles enhance their ability to detect volatile odorants by gular pumping, a rhythmic movement of the floor of the pharynx. Crocodiles appear to have lost their pineal organ but still show signs of melatonin rhythms.

Skin and scales

The skin of crocodilians is clad in non-overlapping scales known as scutes that are covered by beta-keratin. Many of the scutes are strengthened by bony plates known as osteoderms. Scutes are most numerous on the back and neck of the animal. The belly and underside of the tail have rows of broad, flat, square-shaped scales. Between crocodilian scales are hinge areas that consist mainly of alpha-keratin. Underneath the surface, the dermis is thick with collagen. Both the head and jaws lack scales and are instead covered in tight, keratinised skin that is fused directly to the bones of the skull and which, over time, develop a pattern of cracks as the skull develops. The skin on the neck and sides is loose. The scutes contain blood vessels and may act to absorb or release heat during thermoregulation. Research also suggests alkaline ions released into the blood from the calcium and magnesium in the dermal bones act as a buffer during prolonged submersion when increasing levels of carbon dioxide would otherwise cause acidosis.

Some scutes contain a single pore known as an integumentary sense organ. Crocodiles and gharials have these on large parts of their bodies, while alligators and caimans only have them on the head. Their exact function is not fully understood, but it has been suggested they may be mechanosensory organs. There are prominent, paired integumentary glands in skin folds on the throat, and others in the side walls of the cloaca. Various functions for these have been suggested; they may play a part in communication—indirect evidence suggests they secrete pheromones used in courtship or nesting. The skin of crocodilians is tough and can withstand damage from conspecifics, and the immune system is effective enough to heal wounds within a few days. In the genus Crocodylus, the skin contains chromatophores, allowing animals to change colour from dark to light and vice versa.

Circulation

Crocodilians may have the most-complex vertebrate circulatory system with a four-chambered heart and two ventricles, an unusual trait among extant reptiles. Both have left and right aorta are connected by a hole called the Foramen of Panizza. Like birds and mammals, crocodilians have vessels that separately direct blood flow to the lungs and the rest of the body. They also have unique, cog-teeth-like valves that when interlocked direct blood to the left aorta and away from the lungs, and then around the body. This system may allow the animals to remain submerged for a lengthy period, but this explanation has been questioned. Other possible reasons for the peculiar circulatory system include assistance with thermoregulatory needs, prevention of pulmonary oedema, and quick recovery from metabolic acidosis. Retention of carbon dioxide within the body permits an increase in the rate of gastric acid secretion and thus the efficiency of digestion, and other gastrointestinal organs such as the pancreas, spleen, small intestine, and liver also function more efficiently.

When submerged, a crocodilian’s heart may beat at only once or twice a minute, with little blood flow to the muscle. When it rises and takes a breath, its heart rate almost immediately increases and the muscles receive newly oxygenated blood. Unlike many marine mammals, crocodilians have little myoglobin to store oxygen in their muscles. While diving, an increasing concentration of bicarbonate ions causes haemoglobin in the blood to release oxygen for the muscles.

Respiration

Crocodilians were traditionally thought to breathe like mammals, with airflow tidally moving in and out, but studies published in 2010 and 2013 conclude respiration in crocodilians is more bird-like, with airflow moving in a unidirectional loop within the lungs. During inhalation, air flows through the trachea and into two primary bronchi (airways) that divide into narrower secondary passageways. The air continues to move through these, then into even narrower tertiary airways, and then into other secondary airways that were bypassed the first time. The air then flows back into the primary airways and is exhaled.

In crocodilians, the diaphragmaticus muscle, which is analogous to the diaphragm in mammals, attaches the lungs to the liver and pelvis. During inhalation, the external intercostal muscles expand the ribs, allowing the animal to take in more air, while the ischiopubis muscle causes the hips to swing downwards and push the belly outward, while the diaphragmaticus pulls the liver back. When exhaling, the internal intercostal muscles push the ribs inwards while the rectus abdominis pulls the hips and liver forwards and the belly inward. Crocodilians can also use these muscles to adjust the position of their lungs, controlling their buoyancy in the water. An animal sinks when the lungs are pulled towards the tail and floats when they move back towards the head. This allows them to move through the water without creating disturbances that could alert potential prey. They can also spin and twist by moving their lungs laterally.

When swimming and diving, crocodilians appear to rely on lung volume for buoyancy more than for oxygen storage. Just before diving, the animal exhales to reduce its lung volume and reach negative buoyancy. When diving, the nostrils of a crocodilian shut tight. All species have a palatal valve, a membranous flap of skin at the back of the oral cavity (mouth) that protects the oesophagus and trachea when the animal is underwater. This enables them to open their mouths underwater without drowning. Crocodilians typically remain underwater for up to fifteen minutes, but under ideal conditions, some can hold their breath for up to two hours. The depth to which crocodilians can dive is unknown, but crocodiles can dive to at least 20 m.

Crocodilians vocalize by vibrating vocal folds in the larynx. The folds of the American alligator have a complex morphology consisting of epithelium, lamina propria and muscle. Although crocodilian vocal folds lack the elasticity of mammalian ones, the larynx is still capable of complex motor control similar to that in birds and mammals, and can adequately control its fundamental frequency.

Digestion

Crocodilian teeth can only hold onto prey, and food is swallowed unchewed. The stomach consists of a grinding gizzard and a digestive chamber. Indigestible items are regurgitated as pellets. The stomach is more acidic than that of any other vertebrate and contains ridges for gastroliths, which play a role in the crushing of food. Digestion takes place more quickly at higher temperatures. When digesting a meal, CO2-rich blood near the lungs is redirected to the stomach, supplying more acid for the oxyntic glands. Compared to crocodiles, alligators digest more carbohydrates relative to protein. Crocodilians have a very low metabolic rate and thus low energy requirements. They can withstand extended fasting by living on stored fat. Even recently hatched crocodiles are able to survive 58 days without food, losing 23% of their bodyweight during this time.

Thermoregulation

Crocodilians are ectotherms (‘cold-blooded’), relying mostly on their environment to control their body temperature. The main means of warming is sun’s heat, while immersion in water may either raise its temperature via thermal conduction or cool the animal in hot weather. The main method for regulating its temperature is behavioural; temperate-living alligators may start the day by basking in the sun on land and move into water for the afternoon, with parts of the back breaking the surface so it can still be warmed by the sun. At night, it remains submerged and its temperature slowly falls. The basking period is longer in winter. Tropical crocodiles bask briefly in the morning and move into water for rest of the day. They may return to land at nightfall when the air cools. Animals also cool themselves by gaping the mouth, which cools by evaporation from the mouth lining. By these means, the temperature range of crocodilians is usually maintained between 25 and 35 °C, and mainly stays in the range 30 to 33 °C.

Osmoregulation

All crocodilians need to maintain a suitable concentration of salt in body fluids. Osmoregulation is related to the quantity of salts and water that are exchanged with the environment. Intake of water and salts occurs across the lining of the mouth, when water is drunk, incidentally while feeding, and when present in foods. Water is lost during breathing, and salts and water are lost in the urine and faeces, through the skin, and in crocodiles and gharials via salt-excreting glands on the tongue. The skin is a largely effective barrier for water and ions. Gaping causes water loss by evaporation. Large animals are better able than small ones to maintain homeostasis at times of osmotic stress. Newly hatched crocodilians are much less tolerant of exposure to salt water than are older juveniles, presumably because they have a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio.

The kidneys and excretory system are much the same as those in other reptiles, but crocodilians do not have a bladder. In fresh water, the osmolality (the concentration of solutes that contribute to a solution’s osmotic pressure) in the plasma is much higher than that of the surrounding water. The animals are well-hydrated, the urine in the cloaca is abundant and dilute, and nitrogen is excreted as ammonium bicarbonate. Sodium loss is low and mainly occurs through the skin in freshwater conditions. In seawater, the opposite is true; the osmolality in the plasma is lower than that of the surrounding water, causing the animal to dehydrate. The cloacal urine is much more concentrated, white, and opaque, and nitrogenous waste is mostly excreted as insoluble uric acid.

Distribution and habitat

Crocodilians are amphibious, living both in water and on land. The last-surviving, fully terrestrial genus Mekosuchus became extinct about 3,000 years ago after humans had arrived on the Pacific islands it inhabited, making the extinction possibly anthropogenic. Crocodilians are typically creatures of the tropics; the main exceptions are the American and Chinese alligators, whose ranges are the southeastern United States and the Yangtze River, respectively. Florida, United States, is the only place where the ranges of crocodiles and alligators coincide. Crocodilians live almost exclusively in lowland habitiat, and do not appear to live above 1,000 m. With a range extending from eastern India to New Guinea and northern Australia, the saltwater crocodile is the widest-spread species.

Crocodilians use various types of aquatic habitats. Due to their diet, gharials are found in pools and backwaters of rapidly flowing rivers. Caimans prefer warm, turbid lakes and ponds, and slow-moving parts of rivers, although the dwarf caiman inhabits cool, relatively clear, fast-flowing waterways, often near waterfalls. The Chinese alligator is found in slow-moving, turbid rivers that flow across China’s floodplains. The highly adaptable American alligator is found in swamps, rivers and lakes with clear or turbid water. Crocodiles live in marshes, lakes and rivers, and can live in saline environments including estuaries and mangrove swamps. American and saltwater crocodiles swim out to sea. Several extinct species, including the recently extinct Ikanogavialis papuensis, which occurred in coastlines of the Solomon Islands, had marine habitats. Climatic factors locally affect crocodilians’ distribution. During the dry season, caimans can be restricted for several months to deep pools in rivers; in the rainy season, much of the savanna in the Orinoco Llanos is flooded, and they disperse widely across the plain. West African crocodiles in the deserts of Mauritania mainly live in gueltas and floodplains but they retreat underground and to rocky shelters, and enter aestivation during the driest periods.

Crocodilians also use terrestrial habitats such as forests, savannas, grasslands and deserts. Dry land is used for basking, nesting and escaping from temperature extremes. Several species make use of shallow burrows on land to keep cool or warm, depending on the environment. Four species of crocodilians climb trees to bask in areas lacking a shoreline. Tropical rainforests bordering rivers and lakes inhabited by crocodilians are of great importance to them, creating microhabitats where they can flourish. The roots of the trees absorb rainwater and slowly release it back into the environment. This keeps crocodilian habitat moist during the dry season while preventing flooding during the wet season.

Behaviour

Adult crocodilians are typically territorial and solitary. Individuals may guard basking spots, nesting sites, feeding areas, nurseries, and overwintering sites. Male saltwater crocodiles defend areas with several female nesting sites year-round. Some species are occasionally gregarious, particularly during droughts, when several individuals gather at remaining water sites. Individuals of some species may share basking sites at certain times of the day.

Feeding

Crocodilians are largely carnivorous. The diets of species varies with snout shape and tooth sharpness. Species with sharp teeth and long, slender snouts, like the Indian gharial and Australian freshwater crocodile, are specialized for snapping fish, insects, and crustaceans. Extremely broad-snouted species with blunt teeth, like the Chinese alligator and the broad-snouted caiman, are equipped for crushing hard-shelled molluscs. Species whose snouts and teeth are intermediate between these two forms, such as the saltwater crocodile and American alligator, have generalized diets and opportunistically feed on invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Though mostly carnivorous, several species of crocodilian have been observed consuming fruit, and this may play a role in seed dispersal.

In general, crocodilians are stalk-and-ambush predators, though hunting strategies vary between species an their prey. Terrestrial prey is stalked from the water’s edge, and grabbed and drowned. Gharials and other fish-eating species sweep their jaws from side-to-side to snatch prey; these animals can leap out of water to catch birds, bats and leaping fish. A small prey animal can be killed by whiplash as the predator shakes its head. When foraging for fish in shallow water, caiman use their tails and bodies to herd fish and may dig for bottom-dwelling invertebrates. The smooth-fronted caiman will leave water to hunt terrestrial prey.

Crocodilians are unable to chew and need to swallow food whole, so prey that is too large to swallow is torn into pieces. Crocodilians may be unable to deal with a large animal with a thick hide, and may wait until it becomes putrid and comes apart more easily. To tear a chunk of tissue from a large carcass, a crocodilian continuously spins its body while holding prey with its jaws, a manoeuvre that is known as the death roll. During cooperative feeding, some individuals may hold onto prey while others perform the roll. The animals do not fight, and each retires with a piece of flesh and awaits its next feeding turn. After feeding together, individuals may depart alone. Crocodilians typically consume prey with their heads above water. The food is held with the tips of the jaws, tossed towards the back of the mouth by an upward jerk of the head and then gulped down. There is no hard evidence crocodilians cache kills for later consumption.

Reproduction and parenting

Crocodilians are generally polygynous, and individual males try to mate with as many females as they can. Monogamous pairings of American alligators have been recorded. Dominant male crocodilians patrol and defend territories, which contain several females. Males of some species, like the American alligator, try to attract females with elaborate courtship displays. During courtship, crocodilian males and females may rub against each other, circle around, and perform swimming displays. Copulation typically occurs in water. When a female is ready to mate, she arches her back while her head and tail dip underwater. The male rubs across the female’s neck and grasps her with his hindlimbs, and places his tail underneath hers so their cloacas align and his penis can be inserted. Intermission can last up to 15 minutes, during which time the pair continuously submerge and surface. While dominant males usually monopolise females, single American alligator clutches can be sired by three different males.

Depending on the species, female crocodilians may construct either holes or mounds as nests, the latter made from vegetation, litter, sand or soil. Nests are typically found near dens or caves. Those made by different females are sometimes close to each other, particularly in hole-nesting species. Clutches may contain between ten and fifty eggs. Crocodilian eggs are protected by hard shells made of calcium carbonate. The incubation period is two to three months. The sex of the developing, incubating young is temperature dependant; constant nest temperatures above 32 °C produce more males, while those below 31 °C produce more females. Sex in crocodilians may be established in a short period of time, and nests are subject to changes in temperature. Most natural nests produce hatchlings of both sexes, though single-sex clutches occur.

All of the hatchlings in a clutch may leave the nest on the same night. Crocodilians are unusual among reptiles in the amount of parental care provided after the young hatch. The mother helps excavate hatchlings from the nest and carries them to water in her mouth. Newly hatched crocodilians gather together and follow their mother. Both male and female adult crocodilians will respond to vocalizations by hatchlings. Female spectacled caimans in the Venezuelan Llanos are known to leave their young in nurseries or crèches, and one female guards them. Hatchlings of some species tend to bask in a group during the day and start to forage separately in the evening. The time it takes young crocodilians to reach independence can vary. For American alligators, groups of young associate with adults for one-to-two years while juvenile saltwater and Nile crocodiles become independent in a few months.

Communication

Crocodilians are the most vocal of the non-avian reptiles. They can communicate with sounds, including barks, bellows, chirps, coughs, growls, grunts, hisses, moos, roars, toots and whines. Young start communicating with each other before they are hatched. It has been shown the young will repeat, one after another, a light tapping noise near the nest. This early communication may help young to hatch simultaneously. After breaking out of the egg, a juvenile produces yelps and grunts, either spontaneously or as a result of external stimuli. Even unrelated adults respond quickly to juvenile distress calls.

Juveniles are highly vocal, both when scattering in the evening and congregating in the morning. Nearby adults, presumably the parents, may warn young of predators or alert them to the presence of food. The range and quantity of vocalisations vary between species. Alligators and caimans are the noisiest while some crocodile species are almost completely silent. In some crocodile species, individuals “roar” at others when they get too close. The American alligator is exceptionally noisy; it emits a series of up to seven throaty bellows, each a couple of seconds long, at ten-second intervals. It also makes various grunts, growls and hisses. Males create vibrations in water to send out infrasonic signals that attract females and intimidate rivals. The enlarged boss of the male gharial may serve as a sound resonator.

The head slap is another form of acoustic communication. This typically starts when an animal in water elevates its snout and remaining stationary. After some time, the jaws are sharply opened then clamped shut with a biting motion that makes a loud, slapping sound that is immediately followed by a loud splash, after which the head may immerse below the surface and blow bubbles from the throat or nostrils. Some species then roar while others slap water with their tails. Episodes of head slapping spread through the group. The purpose varies and it seems have a social function, and is also used in courtship. Dominant individuals intimidate rivals by swimming at the surface and displaying their large body size, and subordinates submit by holding their head forward above water with the jaws open and then flee below.

Growth and mortality

Eggs and hatchlings have a high death rate, and nests face threats from floods, drying, overheating, and predators. Flooding is a major cause of failure of crocodilians to successfully breed; nests are submerged, developing embryos are deprived of oxygen and juveniles are swept away. Despite the maternal care they receive, eggs and hatchlings are commonly lost to predation. Predators, both mammalian and reptilian, may raid nests and eat crocodilian eggs. After hatching and reaching water, young are still under threat.

In addition to terrestrial predators, young are subject to aquatic attacks by fish. Birds take their toll, and malformed individuals are unlikely to survive. In northern Australia, the survival rate for saltwater crocodile hatchlings is 25 percent but this improves with each year of life, reaching up to 60 percent by year five. Mortality rates among subadults and adults are low, though they are occasionally preyed upon by large cats and snakes. Elephants and hippopotamuses may defensively kill crocodiles. Authorities are uncertain how much cannibalism occurs among crocodilians. Adults do not normally eat their own offspring but there is some evidence of subadults feeding on juveniles, while subadults may be preyed on by adults. Adults appear more likely to protect juveniles and may chase away subadults from nurseries. Rival male Nile crocodiles sometimes kill each other during the breeding season.

Growth in hatchlings and young crocodilians depends on the food supply. Animals reach sexual maturity at a certain length, regardless of age. Saltwater crocodiles reach maturity at 2.2–2.5 m for females and 3 m for males. Australian freshwater crocodiles take ten years to reach maturity at 1.4 m. The spectacled caiman matures earlier, reaching its mature length of 1.2 m in four to seven years. Crocodilians continue to grow throughout their lives; males in particular continue to gain weight as they age, but this is mostly in the form of extra girth rather than length. Crocodilians can live for 35–75 years; their age can be determined by growth rings in their bones.