(Caudata)

Salamanders

Хвостаті земноводні

Salamanders are any members of a group of about 740 species of amphibians that have tails and constitute the order Caudata. The order comprises 10 families, among which are newts and salamanders proper (family Salamandridae) as well as hellbenders, mud puppies, and lungless salamanders. They most commonly occur in freshwater and damp woodlands, principally in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The skin lacks scales and is moist and smooth to the touch, except in newts of the Salamandridae, which may have velvety or warty skin, wet to the touch. The skin may be drab or brightly colored, exhibiting various patterns of stripes, bars, spots, blotches, or dots. Male newts become dramatically colored during the breeding season. Cave species dwelling in darkness lack pigmentation and have a translucent pink or pearlescent appearance.

Salamanders range in size from the minute salamanders, with a total length of 27 mm, including the tail, to the Chinese giant salamander which reaches 1.8 m and weighs up to 65 kg. All the largest species are found in the four families giant salamanders, sirens, Congo eels and Proteidae, who are all aquatic and obligate paedomorphs. Some of the largest terrestrial salamanders, which goes through full metamorphosis, belongs to the family of Pacific giant salamanders, and are much smaller. Most salamanders are between 10 and 20 cm in length.

Trunk, limbs and tail

An adult salamander generally resembles a small lizard, having a basal tetrapod body form with a cylindrical trunk, four limbs, and a long tail. Except in the family Salamandridae, the head, body, and tail have a number of vertical depressions in the surface which run from the mid-dorsal region to the ventral area and are known as costal grooves. Their function seems to be to help keep the skin moist by channeling water over the surface of the body.

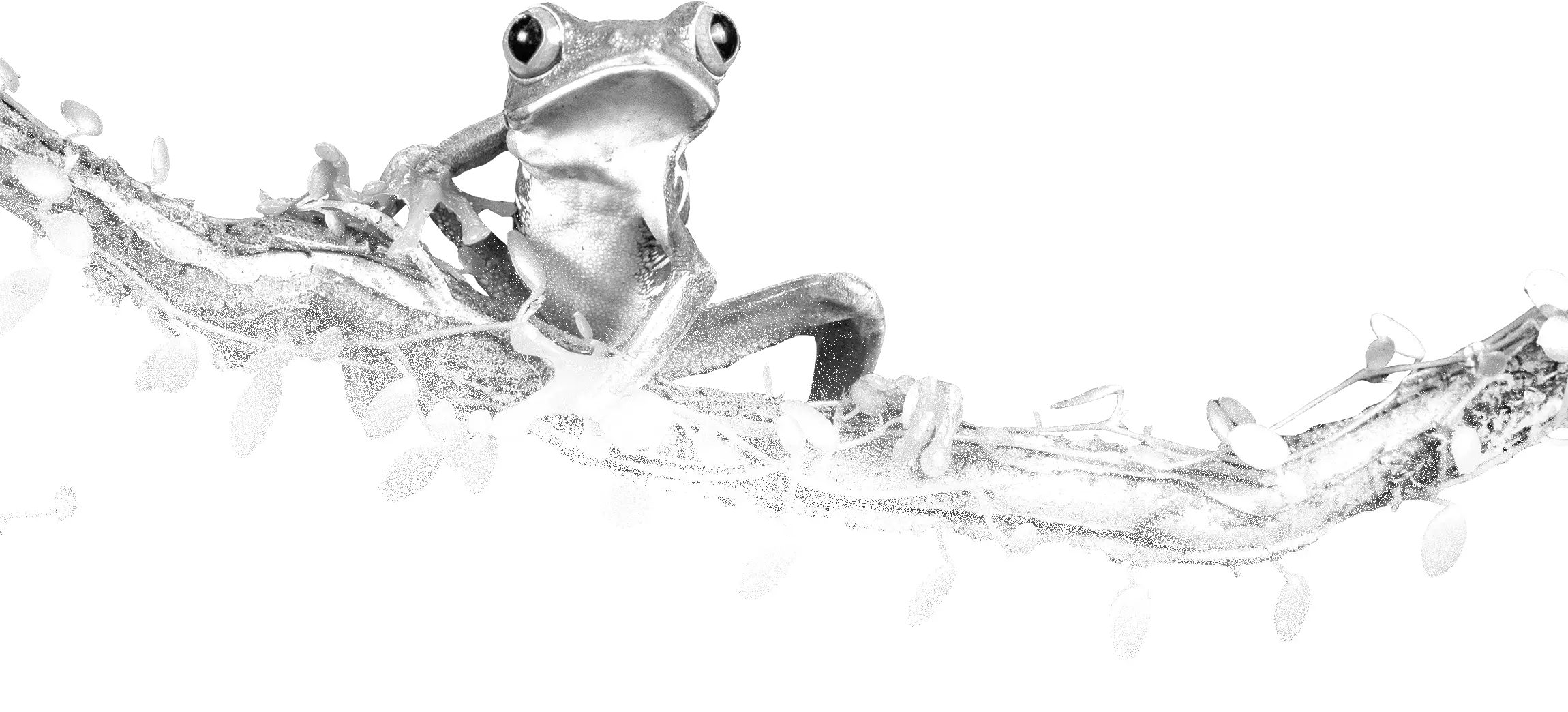

Some aquatic species, such as sirens and amphiumas, have reduced or absent hind limbs, giving them an eel-like appearance, but in most species, the front and rear limbs are about the same length and project sideward, barely raising the trunk off the ground. The feet are broad with short digits, usually four on the front feet and five on the rear. Salamanders do not have claws, and the shape of the foot varies according to the animal’s habitat. Climbing species have elongated, square-tipped toes, while rock-dwellers have larger feet with short, blunt toes. The tree-climbing salamander (Bolitoglossa sp.) has plate-like webbed feet which adhere to smooth surfaces by suction, while the rock-climbing Hydromantes species from California have feet with fleshy webs and short digits and use their tails as an extra limb. When ascending, the tail props up the rear of the body, while one hind foot moves forward and then swings to the other side to provide support as the other hind foot advances.

In larvae and aquatic salamanders, the tail is laterally flattened, has dorsal and ventral fins, and undulates from side to side to propel the animal through the water. In the families Ambystomatidae and Salamandridae, the male’s tail, which is larger than that of the female, is used during the amplexus embrace to propel the mating couple to a secluded location. In terrestrial species, the tail moves to counterbalance the animal as it runs, while in the arboreal salamander and other tree-climbing species, it is prehensile. The tail is also used by certain plethodontid salamanders that can jump, to help launch themselves into the air. The tail is used in courtship and as a storage organ for proteins and lipids. It also functions as a defense against predation, when it may be lashed at the attacker or autotomised when grabbed. Unlike frogs, an adult salamander is able to regenerate limbs and its tail when these are lost.

Skin

The skin of salamanders, in common with other amphibians, is thin, permeable to water, serves as a respiratory membrane, and is well-supplied with glands. It has highly cornified outer layers, renewed periodically through a skin shedding process controlled by hormones from the pituitary and thyroid glands. During moulting, the skin initially breaks around the mouth, and the animal moves forward through the gap to shed the skin. When the front limbs have been worked clear, a series of body ripples pushes the skin toward the rear. The hind limbs are extracted and push the skin farther back, before it is eventually freed by friction as the salamander moves forward with the tail pressed against the ground. The animal often then eats the resulting sloughed skin.

Glands in the skin discharge mucus which keeps the skin moist, an important factor in skin respiration and thermoregulation. The sticky layer helps protect against bacterial infections and molds, reduces friction when swimming, and makes the animal slippery and more difficult for predators to catch. Granular glands scattered on the upper surface, particularly the head, back, and tail, produce repellent or toxic secretions. Some salamander toxins are particularly potent. The rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) produces the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin, the most toxic nonprotein substance known. Handling the newts does no harm, but ingestion of even a minute fragment of skin is deadly. In feeding trials, fish, frogs, reptiles, birds, and mammals were all found to be susceptible.

Mature adults of some salamander species have “nuptial” glandular tissue in their cloacae, at the base of their tails, on their heads or under their chins. Some females release chemical substances, possibly from the ventral cloacal gland, to attract males, but males do not seem to use pheromones for this purpose. In some plethodonts, males have conspicuous mental glands on the chin which are pressed against the females’ nostrils during the courtship ritual. They may function to speed up the mating process, reducing the risk of its being disrupted by a predator or rival male. The gland at the base of the tail in Plethodon cinereus is used to mark fecal pellets to proclaim territorial ownership.

Smell

Olfaction in salamanders plays a role in territory maintenance, the recognition of predators, and courtship rituals, but is probably secondary to sight during prey selection and feeding. Salamanders have two types of sensory areas that respond to the chemistry of the environment. Olfactory epithelium in the nasal cavity picks up airborne and aquatic odors, while adjoining vomeronasal organs detect nonvolatile chemical cues, such as tastes in the mouth. In plethodonts, the sensory epithelium of the vomeronasal organs extends to the nasolabial grooves, which stretch from the nostrils to the corners of the mouth. These extended areas seem to be associated with the identification of prey items, the recognition of conspecifics, and the identification of individuals.

Vision

The eyes of most salamanders are adapted primarily for vision at night. In some permanently aquatic species, they are reduced in size and have a simplified retinal structure, and in cave dwellers such as the Georgia blind salamander, they are absent or covered with a layer of skin. In amphibious species, the eyes are a compromise and are nearsighted in air and farsighted in water. Fully terrestrial species such as the fire salamander have a flatter lens which can focus over a much wider range of distances. To find their prey, salamanders use trichromatic color vision extending into the ultraviolet range, based on three photoreceptor types that are maximally sensitive around 450, 500, and 570 nm. The larvae, and the adults of some highly aquatic species, also have a lateral line organ, similar to that of fish, which can detect changes in water pressure.

Hearing

All salamanders lack middle ear cavity, eardrum and eustachian tube, but have an opercularis system like frogs, and are still able to detect airborne sound. The opercularis system consists of two ossicles: the columella (equivalent to the stapes of higher vertebrates) which is fused to the skull, and the operculum. An opercularis muscle connects the latter to the pectoral girdle, and is kept under tension when the animal is alert. The system seems able to detect low-frequency vibrations (500–600 Hz), which may be picked up from the ground by the fore limbs and transmitted to the inner ear. These may serve to warn the animal of an approaching predator.

Vocalization

Salamanders are usually considered to have no voice and do not use sound for communication in the way that frogs do. Before mating, they communicate by pheromone signaling; some species make quiet ticking, clicking, squeaks or popping noises, perhaps by the opening and closing of valves in the nose. Most salamanders lack vocal cords, but a larynx is present in the mudpuppy (Necturus) and some other species, and the Pacific giant salamanders and a few others have a large larynx and bands known as plicae vocales. The California giant salamander can produce a bark or rattle, and a few species can squeak by contracting muscles in the throat. The arboreal salamander can squeak using a different mechanism; it retracts its eyes into its head, forcing air out of its mouth. The ensatina salamander occasionally makes a hissing sound, while the sirens sometimes produce quiet clicks, and can resort to faint shrieks if attacked. Similar clicking behaviour was observed in two European newts Lissotriton vulgaris and Ichthyosaura alpestris in their aquatic phase. Vocalization in salamanders has been little studied and the purpose of these sounds is presumed to be the startling of predators.

Respiration

Respiration differs among the different species of salamanders, and can involve gills, lungs, skin, and the membranes of mouth and throat. Larval salamanders breathe primarily by means of gills, which are usually external and feathery in appearance. Water is drawn in through the mouth and flows out through the gill slits. Some neotenic species such as the mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus) retain their gills throughout their lives, but most species lose them at metamorphosis. The embryos of some terrestrial lungless salamanders, such as Ensatina, that undergo direct development, have large gills that lie close to the egg’s surface.

When present in adult salamanders, lungs vary greatly among different species in size and structure. In aquatic, cold-water species like the torrent salamanders (Rhyacotriton), the lungs are very small with smooth walls, while species living in warm water with little dissolved oxygen, such as the lesser siren (Siren intermedia), have large lungs with convoluted surfaces. In the lungless salamanders (family Plethodontidae and the clawed salamanders in the family of Asiatic salamanders), no lungs or gills are present, and gas exchange mostly takes place through the skin, known as cutaneous respiration, supplemented by the tissues lining the mouth. To facilitate this, these salamanders have a dense network of blood vessels just under the skin and in the mouth.

In the amphiumas, metamorphosis is incomplete, and they retain one pair of gill slits as adults, with fully functioning internal lungs. Some species that lack lungs respire through gills. In most cases, these are external gills, visible as tufts on either side of the head. Some terrestrial salamanders have lungs used in respiration, although these are simple and sac-like, unlike the more complex organs found in mammals. Many species, such as the olm, have both lungs and gills as adults.

In the Necturus, external gills begin to form as a means of combating hypoxia in the egg as egg yolk is converted into metabolically active tissue. Molecular changes in the mudpuppy during post-embryonic development primarily due to the thyroid gland prevent the internalization of the external gills as seen in most salamanders that undergo metamorphosis. The external gills seen in salamanders differs greatly from that of amphibians with internalized gills. Unlike amphibians with internalized gills which typically rely on the changing of pressures within the buccal and pharyngeal cavities to ensure diffusion of oxygen onto the gill curtain, neotenic salamanders such as Necturus use specified musculature, such as the levatores arcuum, to move external gills to keep the respiratory surfaces constantly in contact with new oxygenated water.

Feeding and diet

Salamanders are opportunistic predators. They are generally not restricted to specific foods, but feed on almost any organism of a reasonable size. Large species such as the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus) eat crabs, fish, small mammals, amphibians, and aquatic insects. In a study of smaller dusky salamanders (Desmognathus) in the Appalachian Mountains, their diet includes earthworms, flies, beetles, beetle larvae, leafhoppers, springtails, moths, spiders, grasshoppers, and mites. Cannibalism sometimes takes place, especially when resources are short or time is limited. Tiger salamander tadpoles in ephemeral pools sometimes resort to eating each other, and are seemingly able to target unrelated individuals. Adult blackbelly salamanders (Desmognathus quadramaculatus) prey on adults and young of other species of salamanders, while their larvae sometimes cannibalise smaller larvae.

Most species of salamander have small teeth in both their upper and lower jaws. Unlike frogs, even the larvae of salamanders possess these teeth. Although larval teeth are shaped like pointed cones, the teeth of adults are adapted to enable them to readily grasp prey. The crown, which has two cusps (bicuspid), is attached to a pedicel by collagenous fibers. The joint formed between the bicuspid and the pedicel is partially flexible, as it can bend inward, but not outward. When struggling prey is advanced into the salamander’s mouth, the teeth tips relax and bend in the same direction, encouraging movement toward the throat, and resisting the prey’s escape. Many salamanders have patches of teeth attached to the vomer and the palatine bones in the roof of the mouth, and these help to retain prey. All types of teeth are resorbed and replaced at intervals throughout the animal’s life.

A terrestrial salamander catches its prey by flicking out its sticky tongue in an action that takes less than half a second. In some species, the tongue is attached anteriorly to the floor of the mouth, while in others, it is mounted on a pedicel. It is rendered sticky by secretions of mucus from glands in its tip and on the roof of the mouth. High-speed cinematography shows how the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) positions itself with its snout close to its prey. Its mouth then gapes widely, the lower jaw remains stationary, and the tongue bulges and changes shape as it shoots forward. The protruded tongue has a central depression, and the rim of this collapses inward as the target is struck, trapping the prey in a mucus-laden trough. Here it is held while the animal’s neck is flexed, the tongue retracted and jaws closed. Large or resistant prey is retained by the teeth while repeated protrusions and retractions of the tongue draw it in. Swallowing involves alternate contraction and relaxation of muscles in the throat, assisted by depression of the eyeballs into the roof of the mouth. Many lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae have more elaborate feeding methods. Muscles surrounding the hyoid bone contract to store elastic energy in springy connective tissue, and actually “shoot” the hyoid bone out of the mouth, thus elongating the tongue. Muscles that originate in the pelvic region and insert in the tongue are used to reel the tongue and the hyoid back to their original positions.

An aquatic salamander lacks muscles in the tongue, and captures its prey in an entirely different manner. It grabs the food item, grasps it with its teeth, and adopts a kind of inertial feeding. This involves tossing its head about, drawing water sharply in and out of its mouth, and snapping its jaws, all of which tend to tear and macerate the prey, which is then swallowed.

Though frequently feeding on slow-moving animals like snails, shrimps and worms, sirenids are unique among salamanders for having developed herbivory speciations, such as beak-like jaw ends and extensive intestines. They feed on algae and other soft-plants in the wild, and easily eat offered lettuce.

Defense

Salamanders have thin skins and soft bodies, move rather slowly and might appear vulnerable to opportunistic predation, but have several effective lines of defense. Mucus coating on damp skin makes them difficult to grasp, and the slimy coating may have an offensive taste or be toxic. When attacked by a predator, a salamander may position itself to make the main poison glands face the aggressor. Often, these are on the tail, which may be waggled or turned up and arched over the animal’s back. The sacrifice of the tail may be a worthwhile strategy, if the salamander escapes with its life and the predator learns to avoid that species of salamander in the future.

Skin secretions of the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) fed to rats have been shown to produce aversion to the flavor, and the rats avoided the presentational medium when it was offered to them again. The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) has a ridge of large granular glands down its spine which are able to squirt a fine jet of toxic fluid at its attacker. By angling its body appropriately, it can accurately direct the spray for a distance of up to 80 cm.

The Iberian ribbed newt (Pleurodeles waltl) has another method of deterring aggressors. Its skin exudes a poisonous, viscous fluid and at the same time, the newt rotates its sharply pointed ribs through an angle between 27 and 92°, and adopts an inflated posture. This action causes the ribs to puncture the body wall, each rib protruding through an orange wart arranged in a lateral row. This may provide an aposematic signal that makes the spines more visible. When the danger has passed, the ribs retract and the skin heals.

Although many salamanders have cryptic colors so as to be unnoticeable, others signal their toxicity by their vivid coloring. Yellow, orange, and red are the colors generally used, often with black for greater contrast. Sometimes, the animal postures if attacked, revealing a flash of warning hue on its underside. The red eft, the brightly colored terrestrial juvenile form of the eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens), is highly poisonous. It is avoided by birds and snakes, and can survive for up to 30 minutes after being swallowed (later being regurgitated). The red salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) is a palatable species with a similar coloring to the red eft. Predators that previously fed on it have been shown to avoid it after encountering red efts, an example of Batesian mimicry. Other species exhibit similar mimicry. In California, the palatable yellow-eyed salamander (Ensatina eschscholtzii) closely resembles the toxic California newt (Taricha torosa) and the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa), whereas in other parts of its range, it is cryptically colored. A correlation exists between the toxicity of Californian salamander species and diurnal habits: relatively harmless species like the California slender salamander (Batrachoseps attenuatus) are nocturnal and are eaten by snakes, while the California newt has many large poison glands in its skin, is diurnal, and is avoided by snakes.

Some salamander species use tail autotomy to escape predators. The tail drops off and wriggles around for a while after an attack, and the salamander either runs away or stays still enough not to be noticed while the predator is distracted. The tail regrows with time, and salamanders routinely regenerate other complex tissues, including the lens or retina of the eye. Within only a few weeks of losing a piece of a limb, a salamander perfectly reforms the missing structure.

Distribution and habitat

Salamanders split off from the other amphibians during the mid- to late Permian, and initially were similar to modern members of the Cryptobranchoidea. Their resemblance to lizards is the result of symplesiomorphy, their common retention of the primitive tetrapod body plan, but they are no more closely related to lizards than they are to mammals. Their nearest relatives are the frogs and toads, within Batrachia.

Salamanders are found only in the Holarctic and Neotropical regions, not reaching south of the Mediterranean Basin, the Himalayas, or in South America the Amazon Basin. They do not extend north of the Arctic tree line, with the northernmost Asian species, Salamandrella keyserlingii, which can survive long-term freezing at −55 °C, occurring in the Siberian larch forests of Sakha and the most northerly species in North America, Ambystoma laterale, reaching no farther north than Labrador and Taricha granulosa not beyond the Alaska Panhandle.

There are about 760 living species of salamander. One-third of the known salamander species are found in North America. The highest concentration of these is found in the Appalachian Mountains region, where the Plethodontidae are thought to have originated in mountain streams. Here, vegetation zones and proximity to water are of greater importance than altitude. Only species that adopted a more terrestrial mode of life have been able to disperse to other localities. The northern slimy salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) has a wide range and occupies a habitat similar to that of the southern gray-cheeked salamander (Plethodon metcalfi). The latter is restricted to the slightly cooler and wetter conditions in north-facing cove forests in the southern Appalachians, and to higher elevations above 900 m, while the former is more adaptable, and would be perfectly able to inhabit these locations, but some unknown factor seems to prevent the two species from co-existing.

One species, the Anderson’s salamander, is one of the few species of living amphibians to occur in brackish or salt water.

Reproduction and development

Many salamanders do not use vocalisations, and in most species the sexes look alike, so they use olfactory and tactile cues to identify potential mates, and sexual selection occurs. Pheromones play an important part in the process and may be produced by the abdominal gland in males and by the cloacal glands and skin in both sexes. Males are sometimes to be seen investigating potential mates with their snouts. In Old World newts, Triturus spp., the males are sexually dimorphic and display in front of the females. Visual cues are also thought to be important in some Plethodont species.

Except for terrestrial species in the three families Plethodontidae, Ambystomatidae, and Salamandridae, salamanders mate in water. The mating varies from courtship between a single male and female to explosive group breeding. In the clade Salamandroidea, which makes up about 90% of all species, fertilization is internal. As a general rule, salamanders with internal fertilization have indirect sperm transfer, but in species like the Sardinian brook salamander, the Corsican brook salamander, the Caucasian salamander and the Pyrenean brook salamander, the male transfers his sperm directly into the female cloaca. For the species with indirect sperm transfer, the male deposits a spermatophore on the ground or in the water according to species, and the female picks this up with her vent. The spermatophore has a packet of sperm supported on a conical gelatinous base, and often an elaborate courtship behavior is involved in its deposition and collection. Once inside the cloaca, the spermatozoa move to the spermatheca, one or more chambers in the roof of the cloaca, where they are stored for sometimes lengthy periods until the eggs are laid. In the Asiatic salamanders, the giant salamanders and Sirenidae, which are the most primitive groups, the fertilization is external. In a reproductive process similar to that of typical frogs, the male releases sperm onto the egg mass. These salamanders also have males that exhibit parental care, which otherwise only occur in females with internal fertilization.

Three different types of egg deposition occur. Ambystoma and Taricha spp. spawn large numbers of small eggs in quiet ponds where many large predators are unlikely. Most dusky salamanders (Desmognathus) and Pacific giant salamanders (Dicamptodon) lay smaller batches of medium-sized eggs in a concealed site in flowing water, and these are usually guarded by an adult, normally the female. Many of the tropical climbing salamanders (Bolitoglossa) and lungless salamanders (Plethodontinae) lay a small number of large eggs on land in a well-hidden spot, where they are also guarded by the mother. Some species such as the fire salamanders (Salamandra) are ovoviviparous, with the female retaining the eggs inside her body until they hatch, either into larvae to be deposited in a water body, or into fully formed juveniles.

In temperate regions, reproduction is usually seasonal and salamanders may migrate to breeding grounds. Males usually arrive first and in some instances set up territories. Typically, a larval stage follows in which the organism is fully aquatic. The tadpole has three pairs of external gills, no eyelids, a long body, a laterally flattened tail with dorsal and ventral fins and in some species limb-buds or limbs. Pond-type larvae may have a pair of rod-like balancers on either side of the head, long gill filaments and broad fins. Stream-type larvae are more slender with short gill filaments—in Rhyacotriton and Onychodactylus, and some species in Batrachuperus, the gills and gill rakers are extremely reduced, narrower fins and no balancers, but instead have hind limbs already developed when they hatch. The tadpoles are carnivorous and the larval stage may last from days to years, depending on species. Sometimes this stage is completely bypassed, and the eggs of most lungless salamanders (Plethodontidae) develop directly into miniature versions of the adult without an intervening larval stage.

By the end of the larval stage, the tadpoles already have limbs and metamorphosis takes place normally. In salamanders, this occurs over a short period of time and involves the closing of the gill slits and the loss of structures such as gills and tail fins that are not required as adults. At the same time, eyelids develop, the mouth becomes wider, a tongue appears, and teeth are formed. The aqueous larva emerges onto land as a terrestrial adult.

Not all species of salamanders follow this path. Neoteny, also known as paedomorphosis, has been observed in all salamander families, and may be universally possible in all salamander species. In this state, an individual may retain gills or other juvenile features while attaining reproductive maturity. The changes that take place at metamorphosis are under the control of thyroid hormones and in obligate neotenes such as the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), the tissues are seemingly unresponsive to the hormones. In other species, the changes may not be triggered because of underactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid mechanism which may occur when conditions in the terrestrial environment are too inhospitable. This may be due to cold or wildly fluctuating temperatures, aridity, lack of food, lack of cover, or insufficient iodine for the formation of thyroid hormones. Genetics may also play a part. The larvae of tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum), for example, develop limbs soon after hatching and in seasonal pools promptly undergo metamorphosis. Other larvae, especially in permanent pools and warmer climates, may not undergo metamorphosis until fully adult in size. Other populations in colder climates may not metamorphose at all, and become sexually mature while in their larval forms. Neoteny allows the species to survive even when the terrestrial environment is too harsh for the adults to thrive on land.