(Chimaeriformes)

Chimaeras

Химероподібні

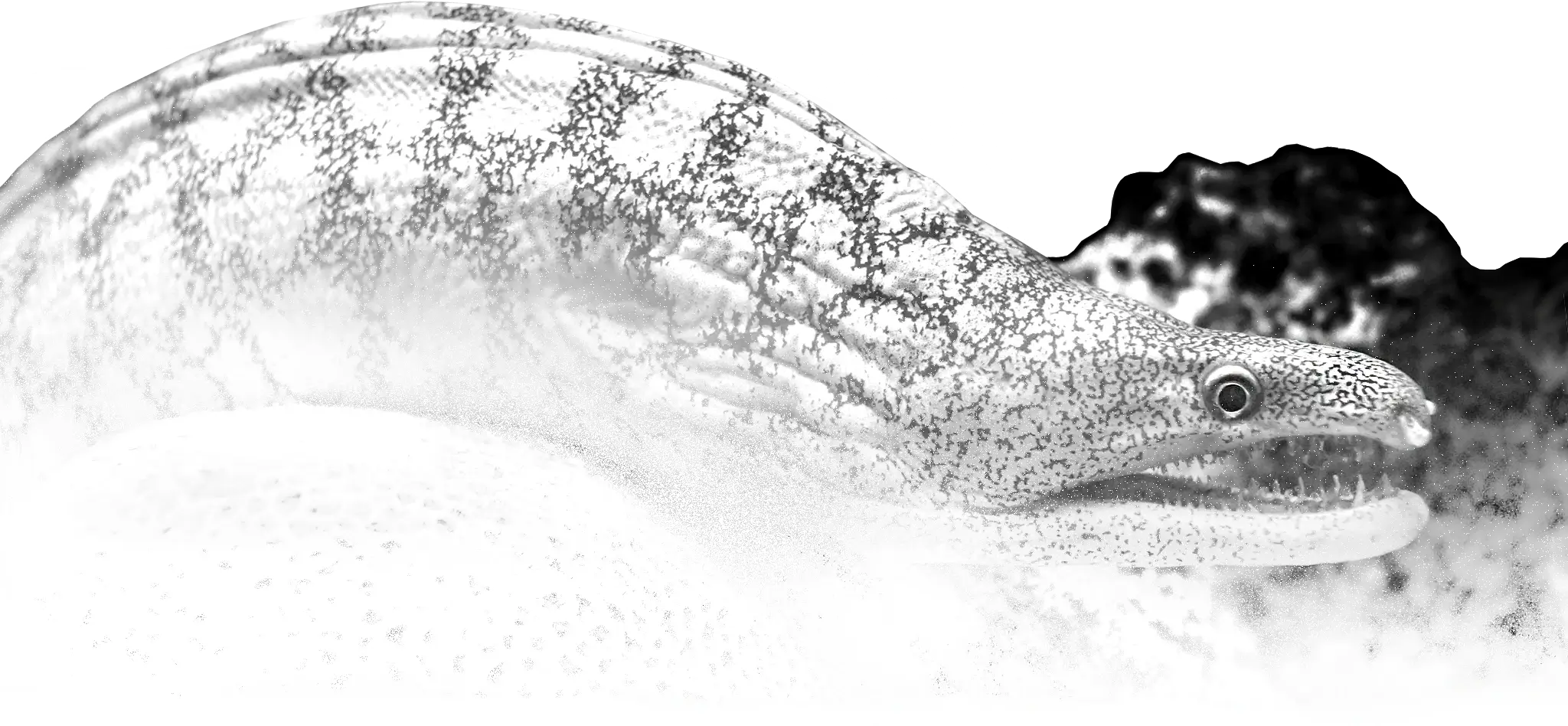

Chimaeras are cartilaginous fish in the order Chimaeriformes, known informally as ghost sharks, rat fish, spookfish, or rabbit fish; the last two names are also applied, respectively, to the ray-finned fish groups of Opisthoproctidae and Siganidae.

At one time a “diverse and abundant” group (based on the fossil record), their closest living relatives are sharks and rays, though their last common ancestor with them lived nearly 400 million years ago. Living species (aside from plough-nose chimaeras) are largely confined to deep water.

Anatomy

Chimaeras are soft-bodied, shark-like fish with bulky heads and long, tapered tails; measured from the tail, they can grow up to 150 cm in length. Like other members of the class Chondrichthyes, chimaera skeletons are entirely cartilaginous, or composed of cartilage. Males use forehead denticles to grasp a female by a fin during copulation. The gill arches are condensed into a pouch-like bundle covered by a sheet of skin (an operculum), with a single gill-opening in front of the pectoral fins.

The pectoral fins are large enough to generate lift at a relaxed forward momentum, giving the chimaera the appearance of “flying” through the water. Further back on the body are also a pair of smaller pelvic fins, and some genera bear an anal fin in front of the tail. In chimaerids and rhinochimaerids, the tail is leptocercal, meaning that it is thin and whip-like, edged from above and below by fins of similar size. In callorhinchids, the tail is instead heterocercal, with a larger upper lobe inclined upwards, similar to many sharks. There are two dorsal fins: a large triangular first dorsal fin and a low rectangular or depressed second dorsal fin. For defense, some chimaeras have a venomous spine on the front edge of the dorsal fin.

In many species, the bulbous snout is modified into an elongated sensory organ, capable of electroreception to find prey. The cartilaginous skull is holostylic, meaning that the palatoquadrate (upper jaw cartilage) is completely fused to the neurocranium (cranial cartilage). This contrasts with modern sharks, where the palatoquadrate is movable and detachable, a trait known as hyostyly. The back of the head is supported by a complex of fused vertebrae called the synarcual, which also connects to the dorsal fin spine.

Instead of sharks’ many sharp, consistently-replaced teeth, chimaeras have just six large, permanent tooth-plates, which grow continuously throughout their entire life. These tooth-plates are arranged in three pairs, with one pair at the tip of the lower jaws and two pairs along the upper jaws. They together form a protruding, beak-like crushing and grinding mechanism, comparable to the incisor teeth of rodents and lagomorphs (hence the name “rabbit fish”). Chimaera teeth are unique among vertebrates, due to their mode of mineralization. Most of each plate is formed by relatively soft osteodentin, but the active edges are supplemented by a unique hypermineralized tissue called pleromin. Pleromin is an extremely hard enamel-like tissue, arranged into sheets or beaded rods, but it is deposited by mesenchyme-derived cells similar to those that form bone. In addition, pleromin’s hardness is due to the mineral whitlockite, which crystalizes within the teeth as the animal matures. Other vertebrates with hypermineralized teeth rely on enamel, which is derived from ameloblasts and encases round crystals of the mineral apatite.

Chimaeras also differ from sharks in that they have separate anal and urogenital openings.

Behavior

Chimaeras live in temperate ocean floors, with some species inhabiting depths exceeding 2,000 m, with relatively few modern species regularly inhabiting shallow water. Exceptions include the members of the genus Callorhinchus, the rabbit fish and the spotted ratfish, which locally or periodically can be found at shallower depths. Consequently, these are also among the few species kept in public aquaria. They live in all the oceans except for the Arctic and Antarctic oceans.

The usual diet of chimaeras consists of crustaceans, ophiuroids, and molluscs. Modern species are demersal durophages, but they used to be more diverse. The Carboniferous period had forms that lived as specialised suction feeders in the water column.

Chimaera reproduction resembles that of sharks in some ways: males employ claspers for internal fertilization of females and females lay eggs within spindle-shaped, leathery egg cases.

Unlike sharks, male chimaeras have retractable sexual appendages (known as tentacula) to assist mating. The frontal tentaculum, a bulbous rod which extends out of the forehead, is used to clutch the females’ pectoral fins during mating. The prepelvic tentacula are serrated hooked plates normally hidden in pouches in front of the pelvic fins, and they anchor the male to the female. Lastly, the pelvic claspers (sexual organs shared by sharks) are fused together by a cartilaginous sheathe before splitting into a pair of flattened lobes at their tip.

As other fish, chimaeras have a number of parasites. Chimaericola leptogaster (Chimaericolidae) is a monogenean parasite of the gills of Chimaera monstrosa; the species can attain 50 mm in length.