(Actinopterygii)

Ray-finned Fishes

Променепері

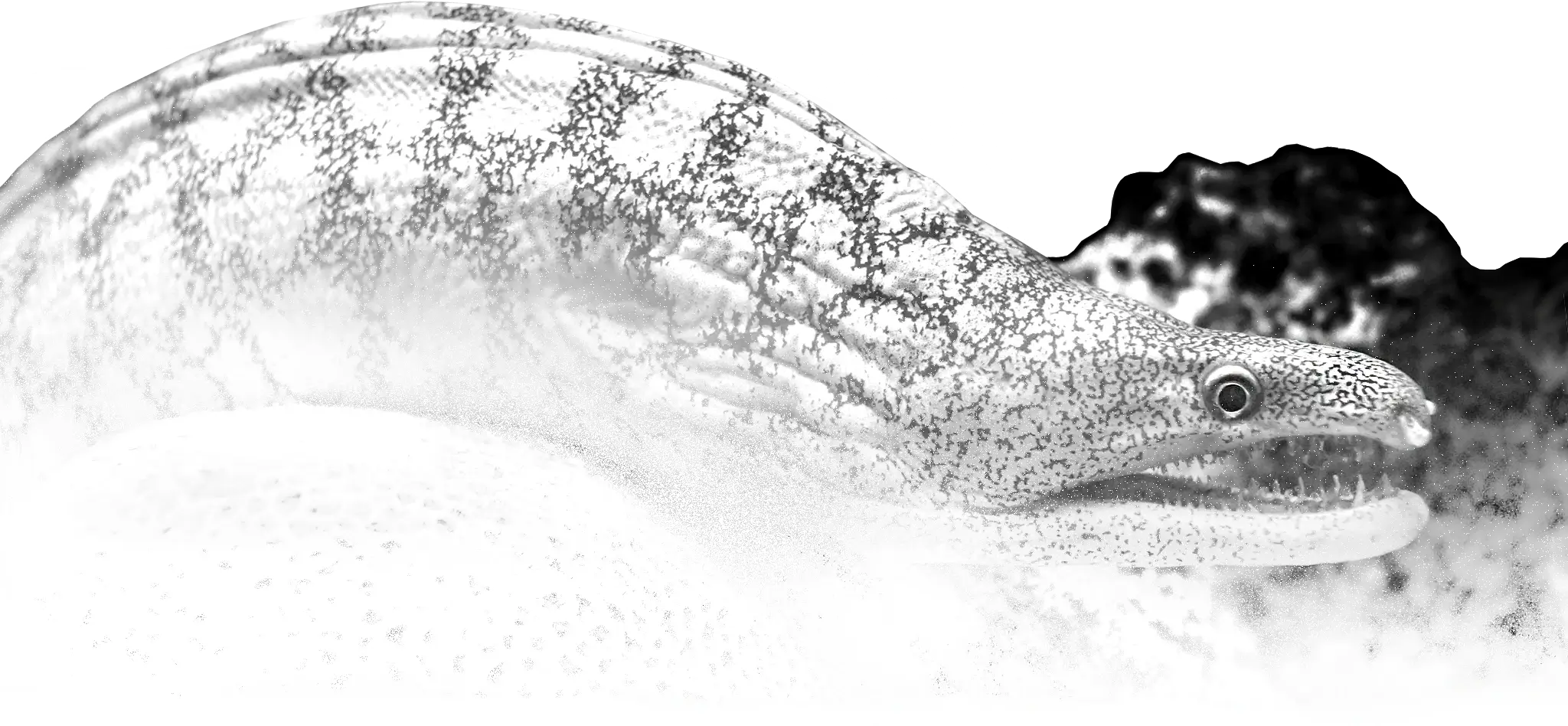

Actinopterygii, members of which are known as ray-finned fish or actinopterygians, is a class of bony fish that comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species. They are so called because of their lightly built fins made of webbings of skin supported by radially extended thin bony spines called lepidotrichia, as opposed to the bulkier, fleshy lobed fins of the sister clade Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish). Resembling folding fans, the actinopterygian fins can easily change shape and wetted area, providing superior thrust-to-weight ratios per movement compared to sarcopterygian and chondrichthyian fins. The fin rays attach directly to the proximal or basal skeletal elements, the radials, which represent the articulation between these fins and the internal skeleton (e.g., pelvic and pectoral girdles).

The vast majority of actinopterygians are teleosts. By species count, they dominate the subphylum Vertebrata, and constitute nearly 99% of the over 30,000 extant species of fish. They are the most abundant nektonic aquatic animals and are ubiquitous throughout freshwater and marine environments from the deep sea to subterranean waters to the highest mountain streams. Extant species can range in size from Paedocypris, at 8 mm; to the massive ocean sunfish, at 2,300 kg; and to the giant oarfish, at 11 m. The largest ever known ray-finned fish, the extinct Leedsichthys from the Jurassic, has been estimated to have grown to 16.5 m.

Characteristics

Ray-finned fishes occur in many variant forms. The main features of typical ray-finned fish are shown in the adjacent diagram.

The swim bladder is a more derived structure and used for buoyancy. Except from the bichirs, which just like the lungs of lobe-finned fish have retained the ancestral condition of ventral budding from the foregut, the swim bladder in ray-finned fishes derives from a dorsal bud above the foregut. In early forms the swim bladder could still be used for breathing, a trait still present in Holostei (bowfins and gars). In some fish like the arapaima, the swim bladder has been modified for breathing air again, and in other lineages it has been completely lost.

The teleosts have urinary and reproductive tracts that are fully separated, while the Chondrostei have common urogenital ducts, and partially connected ducts are found in Cladistia and Holostei.

Ray-finned fishes have many different types of scales; but all teleosts have leptoid scales. The outer part of these scales fan out with bony ridges, while the inner part is crossed with fibrous connective tissue. Leptoid scales are thinner and more transparent than other types of scales, and lack the hardened enamel- or dentine-like layers found in the scales of many other fish. Unlike ganoid scales, which are found in non-teleost actinopterygians, new scales are added in concentric layers as the fish grows.

Teleosts and chondrosteans (sturgeons and paddlefish) also differ from the bichirs and holosteans (bowfin and gars) in having gone through a whole-genome duplication (paleopolyploidy). The WGD is estimated to have happened about 320 million years ago in the teleosts, which on average has retained about 17% of the gene duplicates, and around 180 million years ago in the chondrosteans. It has since happened again in some teleost lineages, like Salmonidae (80–100 million years ago) and several times independently within the Cyprinidae (in goldfish and common carp as recently as 14 million years ago).

Reproduction

In nearly all ray-finned fish, the sexes are separate, and in most species the females spawn eggs that are fertilized externally, typically with the male inseminating the eggs after they are laid. Development then proceeds with a free-swimming larval stage. However other patterns of ontogeny exist, with one of the commonest being sequential hermaphroditism. In most cases this involves protogyny, fish starting life as females and converting to males at some stage, triggered by some internal or external factor. Protandry, where a fish converts from male to female, is much less common than protogyny.

Most families use external rather than internal fertilization. Of the oviparous teleosts, most (79%) do not provide parental care. Viviparity, ovoviviparity, or some form of parental care for eggs, whether by the male, the female, or both parents is seen in a significant fraction (21%) of the 422 teleost families; no care is likely the ancestral condition. The oldest case of viviparity in ray-finned fish is found in Middle Triassic species of †Saurichthys. Viviparity is relatively rare and is found in about 6% of living teleost species; male care is far more common than female care. Male territoriality “preadapts” a species for evolving male parental care.

There are a few examples of fish that self-fertilise. The mangrove rivulus is an amphibious, simultaneous hermaphrodite, producing both eggs and spawn and having internal fertilisation. This mode of reproduction may be related to the fish’s habit of spending long periods out of water in the mangrove forests it inhabits. Males are occasionally produced at temperatures below 19 °C and can fertilise eggs that are then spawned by the female. This maintains genetic variability in a species that is otherwise highly inbred.

Source: Wikipedia