(Gymnophiona)

Caecilians

Безногі земноводні

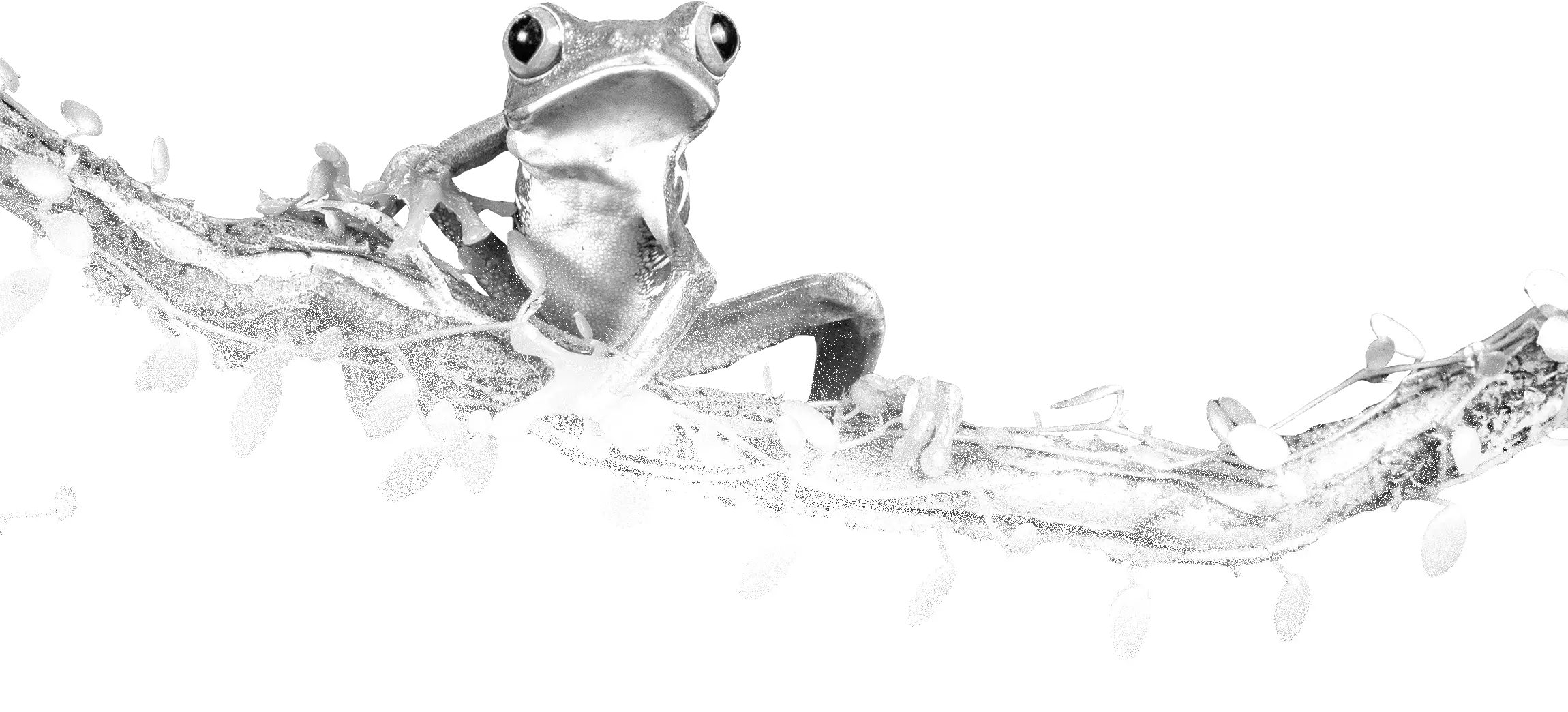

Caecilians are a group of limbless, worm-shaped or snake-shaped amphibians with either small eyes or no eyes. Modern caecilians are a clade, the order Gymnophiona, one of the three living amphibian groups alongside Anura (frogs) and Urodela (salamanders). Gymnophiona is a crown group, encompassing all modern caecilians and all descendants of their last common ancestor. There are more than 220 living species of caecilian classified in 10 families. Gymnophionomorpha is a recently coined name for the corresponding total group which includes Gymnophiona as well as a few extinct stem-group caecilians (extinct amphibians whose closest living relatives are caecilians but are not descended from any caecilian).

Description

Caecilians’ anatomy is highly adapted for a burrowing lifestyle. In a couple of species, belonging to the primitive genus Ichthyophis, vestigial traces of limbs have been found, and in Typhlonectes compressicauda the presence of limb buds has been observed during embryonic development, remnants in an otherwise completely limbless body. This makes the smaller species resemble worms, while the larger species like Caecilia thompsoni, with lengths up to 1.5 m, resemble snakes. Their tails are short or absent, and their cloacae are near the ends of their bodies.

Except for one lungless species, Atretochoana eiselti, all caecilians have lungs, but also use their skin or mouths for oxygen absorption. Often, the left lung is much smaller than the right one, an adaptation to body shape that is also found in snakes.

Their trunk muscles are adapted to pushing their way through the ground, with the vertebral column and its musculature acting as a piston inside the outer layer of the body wall musculature, which is closely attached to the skin. By contracting the outer layer of muscles it squeezes the coelom and generates a strong hydrostatic force that lengthens the body. This muscle system allows the animal to anchor its hind end in position, and force the head forwards, and then pull the rest of the body up to reach it in waves. In water or very loose mud, caecilians instead swim in an eel-like fashion. Caecilians in the family Typhlonectidae are aquatic, and the largest of their kind. The representatives of this family have a fleshy fin running along the rear section of their bodies, which enhances propulsion in water.

Skull and senses

Caecilians have small or absent eyes, with only a single known class of photoreceptors, and their vision is limited to dark-light perception. Unlike other modern amphibians (frogs and salamanders), the skull is compact and solid, with few large openings between plate-like cranial bones. The snout is pointed and bullet-shaped, used to force their way through soil or mud. In most species, the mouth is recessed under the head, so that the snout overhangs the mouth.

The bones in the skull are reduced in number compared to prehistoric amphibian species. Many bones of the skull are fused together: the maxilla and palatine bones have fused into a maxillopalatine in all living caecilians, and the nasal and premaxilla bones fuse into a nasopremaxilla in some families. Some families can be differentiated by the presence or absence of certain skull bones, such as the septomaxillae, prefrontals, an/or a postfrontal-like bone surrounding the orbit (eye socket). The braincase is encased in a fully integrated compound bone called the os basale, which takes up most of the rear and lower parts of the skull. In skulls viewed from above, a mesethmoid bone may be visible in some species, wedging into the midline of the skull roof.

All caecilians have a pair of unique sensory structures, known as tentacles, located on either side of the head between the eyes and nostrils. These are probably used for a second olfactory capability, in addition to the normal sense of smell based in the nose.

The ringed caecilian (Siphonops annulatus) has dental glands that may be homologous to the venom glands of some snakes and lizards. The function of these glands is unknown.

The middle ear consists of only the stapes bone and the oval window, which transfer vibrations into the inner ear through a reentrant fluid circuit as seen in some reptiles. Adults of species in the family Scolecomorphidae lack both a stapes and an oval window, making them the only known amphibians missing all the components of a middle ear apparatus.

The lower jaw is specialized in caecilians. Gymnophionans, including extinct species, have only two components of the jaw: the pseudodentary (at the front, bearing teeth) and pseudoangular (at the back, bearing the jaw joint and muscle attachments). These two components are what remains following fusion between a larger set of bones. An additional inset tooth row with up to 20 teeth lies parallel to the main marginal tooth row of the jaw.

All but the most primitive caecilians have two sets of muscles for closing the jaw, compared with the single pair found in other amphibians. One set of muscles, the adductors, insert into the upper edge of the pseudoangular in front of the jaw joint. Adductor muscles are commonplace in vertebrates, and close the jaw by pulling upwards and forwards. A more unique set of muscles, the abductors, insert into the rear edge of the pseudoangular below and behind the jaw joint. They close the jaw by pulling backwards and downwards. Jaw muscles are more highly developed in the most efficient burrowers among the caecilians, and appear to help keep the skull and jaw rigid.

Skin

Their skin is smooth and usually dark, but some species have colourful skins. Inside the skin are calcite scales. Because of these scales, the caecilians were once thought to be related to the fossil Stegocephalia, but they are now believed to be a secondary development, and the two groups are most likely unrelated. Scales are absent in the families Scolecomorphidae and Typhlonectidae, except the species Typhlonectes compressicauda where minute scales have been found in the hinder region of the body. The skin also has numerous ring-shaped folds, or annuli, that partially encircle the body, giving them a segmented appearance. Like some other living amphibians, the skin contains glands that secrete a toxin to deter predators. The skin secretions of Siphonops paulensis have been shown to have hemolytic properties.

Milk provisioning

Recent research, as documented in the journal Science, has shed light on the behavior of certain species of caecilians. These studies reveal that some caecilians exhibit a phenomenon wherein they provide their hatchlings with a nutrient-rich substance akin to milk, delivered through a maternal vent. Among the species investigated, the oviparous nonmammalian caecilian amphibian Siphonops annulatus stood out, indicating that the practice of lactation may be more widespread among these creatures than previously thought. As detailed in a 2024 study, researchers collected 16 mothers of the Siphonops annulatus species from cacao plantations in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and filmed them with their altricial hatchlings in the lab. The mothers remained with their offspring, which suckled on a white, viscous liquid from their cloaca, experiencing rapid growth in their first week. This milk-like substance, rich in fats and carbohydrates, is produced in the mother’s oviduct epithelium’s hypertrophied glands, similar to mammal milk. The substance was released seemingly in response to tactile and acoustic stimulation by the babies. The researchers observed the hatchlings emitting high-pitched clicking sounds as they approached their mothers for milk, a behavior unique among amphibians. This milk-feeding behavior may contribute to the development of the hatchlings’ microbiome and immune system, similar to mammalian young. The presence of milk production in caecilians that lay eggs suggests an evolutionary transition between egg-laying and live birth.

Distribution

Caecilians are native to wet, tropical regions of Southeast Asia, India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka, parts of East and West Africa, the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean, Central America, and in northern and eastern South America. In Africa, caecilians are found from Guinea-Bissau (Geotrypetes) to southern Malawi (Scolecomorphus), with an unconfirmed record from eastern Zimbabwe. They have not been recorded from the extensive areas of tropical forest in central Africa. In South America, they extend through subtropical eastern Brazil well into temperate northern Argentina. They can be seen as far south as Buenos Aires, when they are carried by the flood waters of the Paraná River coming from farther north. Their American range extends north to southern Mexico. The northernmost distribution is of the species Ichthyophis sikkimensis of northern India. Ichthyophis is also found in South China and Northern Vietnam. In Southeast Asia, they are found as far east as Java, Borneo, and the southern Philippines, but they have not crossed Wallace’s line and are not present in Australia or nearby islands. There are no known caecilians in Madagascar, but their presence in the Seychelles and India has led to speculation on the presence of undiscovered extinct or extant caecilians there.

Reproduction

Caecilians are the only order of amphibians to use internal insemination exclusively (although most salamanders have internal fertilization and the tailed frog in the US uses a tail-like appendage for internal insemination in its fast-flowing water environment). The male caecilians have a long tube-like intromittent organ, the phallodeum, which is inserted into the cloaca of the female for two to three hours. About 25% of the species are oviparous (egg-laying); the eggs are laid in terrestrial nests rather than in water and are guarded by the female. For some species, the young caecilians are already metamorphosed when they hatch; others hatch as larvae. The larvae are not fully aquatic, but spend the daytime in the soil near the water.

About 75% of caecilians are viviparous, meaning they give birth to already-developed offspring. The foetus is fed inside the female with cells lining the oviduct, which they eat with special scraping teeth. Some larvae, such as those of Typhlonectes, are born with enormous external gills which are shed almost immediately.

The egg-laying herpelid species Boulengerula taitana feeds its young by developing an outer layer of skin, high in fat and other nutrients, which the young peel off with modified teeth. This allows them to grow by up to 10 times their own weight in a week. The skin is consumed every three days, the time it takes for a new layer to grow, and the young have only been observed to eat it at night. It was formerly thought that the juveniles subsisted only on a liquid secretion from their mothers. This form of parental care, known as maternal dermatophagy, has also been reported in two species in the family Siphonopidae: Siphonops annulatus and Microcaecilia dermatophaga. Siphonopids and herpelids are not closely related to each other, having diverged in the Cretaceous Period. The presence of maternal dermatophagy in both families suggest that it may be more widespread among caecilians than previously considered.

Herpele squalostoma caecilians vertically transmit the mother’s microbiome to their offspring through maternal dermatophagy. In comparison to other amphibians, the extended parenting of caecilians can provide beneficial bacteria and fungi, but this transmission risks the spread of diseases like chytridiomycosis.

Diet

Caecilians are considered as generalist predators. While caecilians are generally carnivorous, their diet differs between taxa. The stomach contents of wild caecilians include primarily soil ecosystem engineers like earthworms, termites, lizards, moth larvae, and shrimp. Some species of caecilians will opportunistically consume newborn rodents, salmon eggs, and veal in laboratory conditions, as well as vertebrates such as scolecophidian snakes, lizards, small fish, and frogs.