(Tardigrada)

Water Bears

Тихоходи

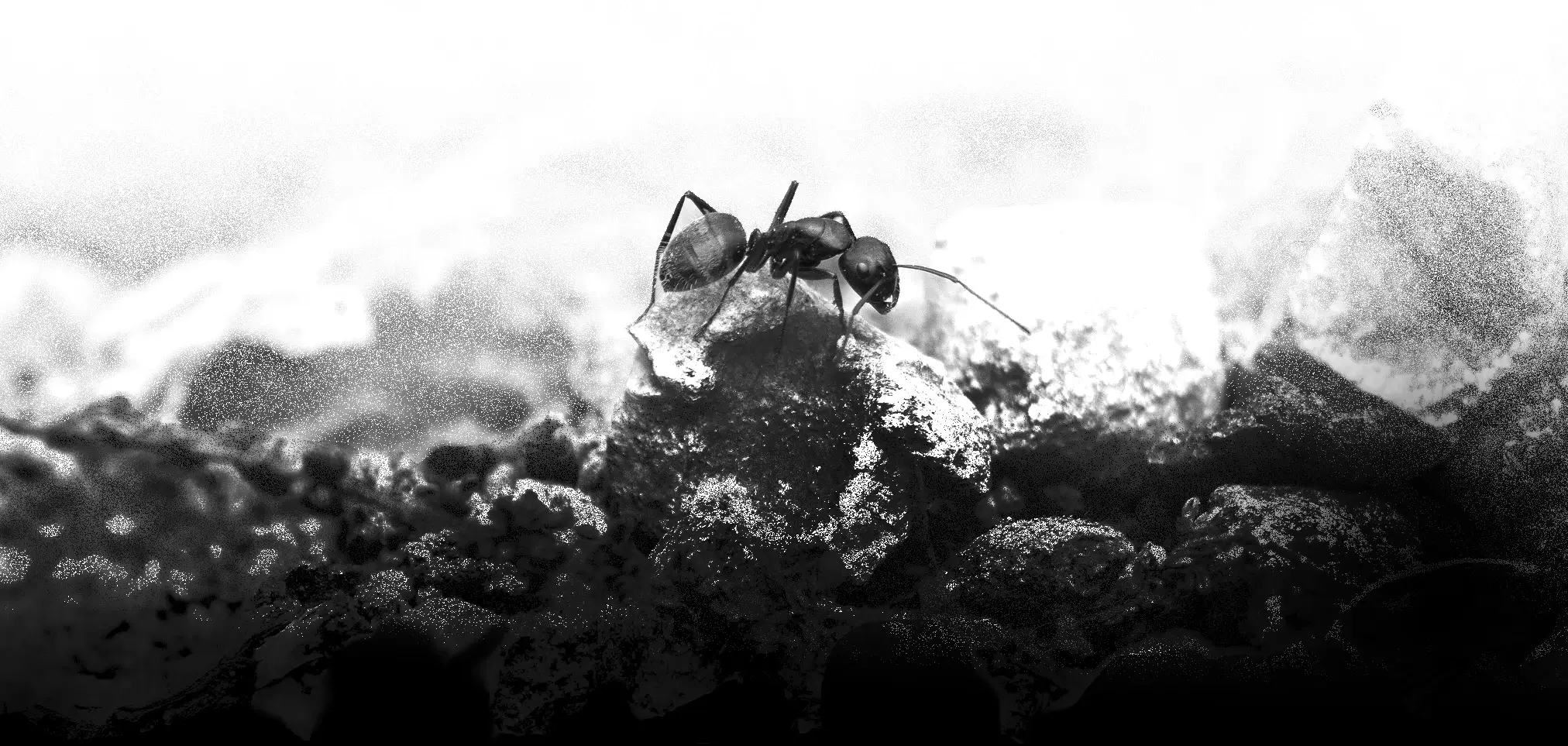

Tardigrades known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. There are about 1,500 known species in the phylum Tardigrada, a part of the superphylum Ecdysozoa.

They live in diverse regions of Earth’s biosphere – mountaintops, the deep sea, tropical rainforests, and the Antarctic. Tardigrades are among the most resilient animals known, with individual species able to survive extreme conditions – such as exposure to extreme temperatures, extreme pressures (both high and low), air deprivation, radiation, dehydration, and starvation – that would quickly kill most other forms of life. Tardigrades have survived exposure to outer space.

Description

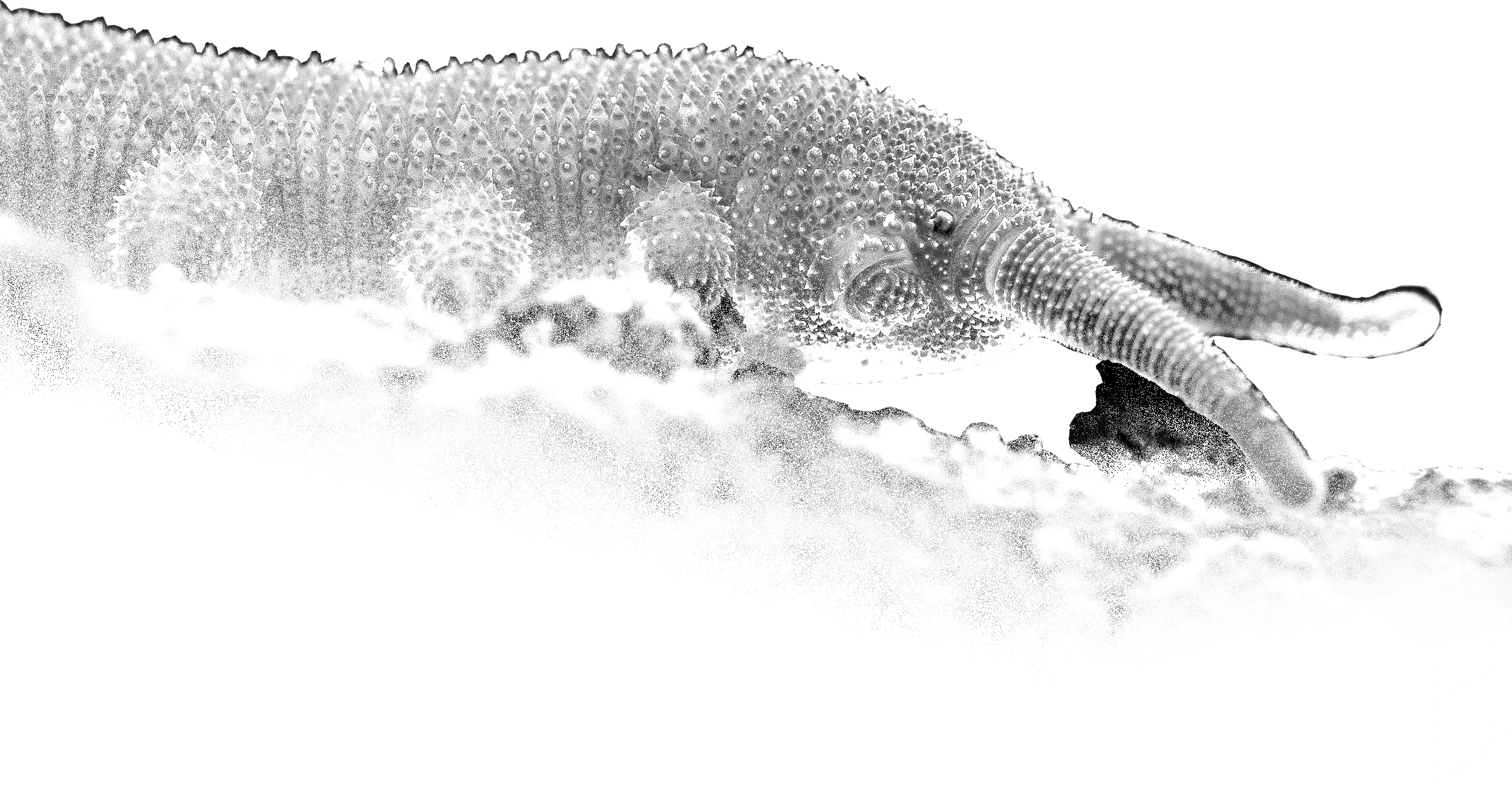

Tardigrades have a short plump body with four pairs of hollow unjointed legs. Most range from 0.1 to 0.5 mm in length, although the largest species may reach 1.3 mm. The body cavity is a haemocoel, an open circulatory system, filled with a colourless fluid. The body covering is a cuticle that is replaced when the animal moults; it contains hardened (sclerotised) proteins and chitin but is not calcified. Each leg ends in one or more claws according to the species; in some species, the claws are modified as sticky pads. In marine species, the legs are telescopic. There are no lungs, gills, or blood vessels, so tardigrades rely on diffusion through the cuticle and body cavity for gas exchange. They are made up of only about 1000 cells.

Tardigrades feed by sucking animal or plant cell fluids, or on detritus. A pair of stylets pierce the prey; the pharynx muscles then pump the fluids from the prey into the gut. A pair of salivary glands secrete a digestive fluid into the mouth, and produce replacement stylets each time the animal moults. Non-marine species have excretory Malpighian tubules where the intestine joins the hindgut. Some species have excretory or other glands between or at the base of the legs.

Most tardigrades have both male and female animals which copulate by a variety of methods. The females lay eggs; those of Austeruseus faeroensis are spherical, 80 μm in diameter, with a knobbled surface. In other species the eggs can be ovoid, as in Hypsibius annulatus, or may be spherical with pyramidal or bottle-shaped surface ornamentation. Some species appear to have no males, suggesting that parthenogenesis is common.

Both sexes have a single gonad (an ovary or testis) located above the intestine. A pair of ducts run from the testis, opening through a single gonopore in front of the anus. Females have a single oviduct opening either just above the anus or directly into the rectum, which forms a cloaca.

The male may place his sperm into the cloaca, or may penetrate the female’s cuticle and place the sperm straight into her body cavity, for it to fertilise the eggs directly in the ovary. A third mechanism in species such as H. annulatus is for the male to place the sperm under the female’s cuticle; when she moults, she lays eggs into the cast cuticle, where they are fertilised. Courtship occurs in some aquatic tardigrades, with the male stroking his partner with his cirri to stimulate her to lay eggs; fertilisation is then external.

Up to 30 eggs are laid, depending on the species. Terrestrial tardigrade eggs have drought-resistant shells. Aquatic species either glue their eggs to a substrate or leave them in a cast cuticle. The eggs hatch within 14 days, the hatchlings using their stylets to open their egg shells.

Ecology and life history

Tardigrades as a group are cosmopolitan, living in many environments on land, in freshwater, and in the sea. Their eggs and resistant life-cycle stages (cysts and tuns) are small and durable enough to enable long-distance transport, whether on the feet of other animals or by the wind.

Individual species have more specialised distributions, many being both regional and limited to a single type of habitat, such as mountains. Some species have wide distributions: for instance, Echiniscus lineatus is pantropical. Halobiotus is restricted to cold Holarctic seas. Species such as Borealibius and Echiniscus lapponicus have a discontinuous distribution, being both polar and on tall mountains. This could be a result of long-distance transport by the wind, or the remains of an ancient geographic range when the climate was colder. A small percentage of species may be cosmopolitan.

The majority of species live in damp habitats such as on lichens, liverworts, and mosses, and directly in soil and leaf litter. In freshwater and the sea they live on and in the bottom, such as in between particles or around seaweeds. More specialised habitats include hot springs and as parasites or commensals of marine invertebrates. In soil there can be as many as 300,000 per square metre; on mosses they can reach a density of over 2 million per square metre.

Tardigrades are host to many microbial symbionts and parasites. In glacial environments, the bacterial genera Flavobacterium, Ferruginibacter, and Polaromonas are common in tardigrades’ microbiomes. Many tardigrades are predatory; Milnesium lagniappe includes other tardigrades such as Macrobiotus acadianus among its prey. Tardigrades consume prey such as nematodes, and are themselves predated upon by soil arthropods including mites, spiders and cantharid beetle larvae.

With the exception of 62 exclusively freshwater species, all non-marine tardigrades are found in terrestrial environments. Because the majority of the marine species belongs to Heterotardigrada, the most ancestral class, the phylum evidently has a marine origin.

Source: Wikipedia