(Gastrotricha)

Hairy-Bellied Worms

Черевовійчасті черви

Phylum Gastrotricha, or hairy-bellied worms, includes approximately 790 currently known species of small, bilaterally symmetrical, acoelomate organisms found in marine, brackish, and fresh waters worldwide. They may constitute 1 to 8% of benthic meiofaunal organisms in marine waters, and can reach densities of over 150 individuals per 10 cm2 in freshwaters, making them one of the most abundant organism groups in both environments. Gastrotrichs may also be semi-terrestrial. There are over 300 species in order Macrodasyida, all but two of which are marine or estuarine, and over 400 species in order Chaetonotida, three-quarters of which are freshwater, the remainder are marine or semi-terrestrial. Both groups are distinguished by the shape and orientation of their pharyngeal lumen. Likewise, macrodasyids have two pores in their pharynx, which expels excess water during feeding. Freshwater species are generally benthic or periphytic, marine species tend to be found in interstitial spaces in loose sediments, a few aquatic species are planktonic, and semi-terrestrial gastrotrichs are found in water films around soil particles. Many species have posterior adhesive tubes that form a pair of projections from the end of their body, while a few have a single, elongated “tail” instead.

Gastrotrichs are found globally in freshwater, marine, and semi-terrestrial environments, although some genera and species have limited local distributions.

Habitat

Many gastrotrich species are found in vegetated areas or in surface sediment. They may be planktonic or benthic, and are found in marine and freshwater environments, including lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Some species are semi-terrestrial, living in water films on land. Most marine species live interstitially, and may even be found in anoxic environments.

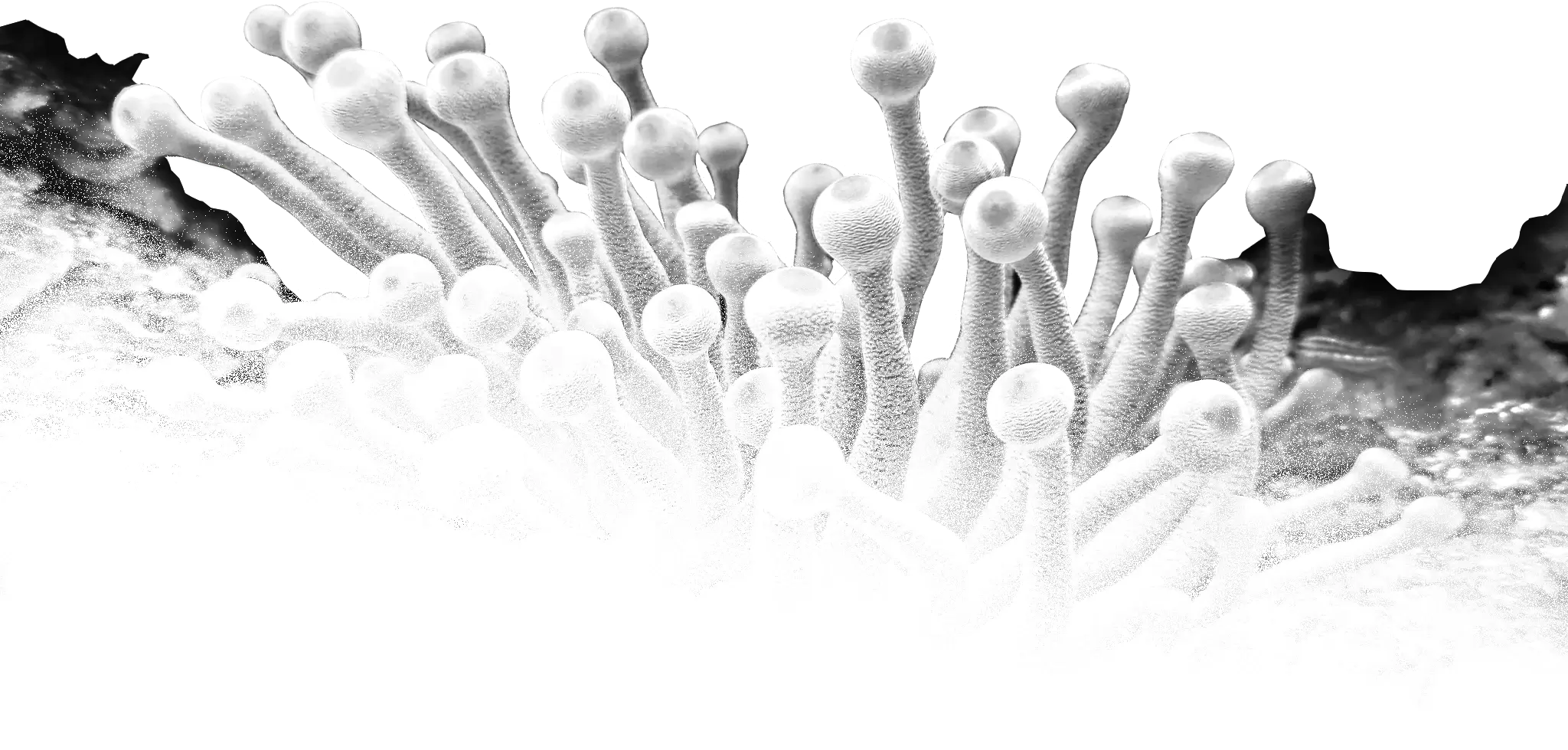

Physical Description

Gastrotrichs are small, 50 to 800 micrometers in length, bilaterally symmetrical, acoelomate organisms, with transparent bodies divided into head and trunk regions. The head bears sensory cilia. Many species have posterior adhesive tubes that form a pair of projections from the end of the body, while a few have a single, elongated “tail”. Species lacking adhesive tubes are planktonic, while those with adhesive tubes use their secretions to temporarily anchor themselves to various substrates. The body, which is spindle or tenpin-shaped and ventrally flattened, is covered with a cuticle that may be composed of a single layer or many layers. The body can be covered with spines, scales, or plates depending on the species, which are derived from the fibrous lower layers of the cuticle. Outer cuticular layers are composed of membrane-like structures. The epidermis is partially syncytial (multiple nuclei without membranes) and partially cellular. The ventral epidermal layer is ciliated, giving members of this phylum their common name, “hairy-bellied worms.”

Gastrotrichs generally feed by generating currents that draw food particles into the mouth, using either pumping actions of their muscular pharynx or ciliary currents. The pharynx leads into the intestine, where enzymes secreted by glandular cells digest the food, and nutrients are absorbed via diffusion; in some species, the pharynx also has multiple tubes that connect the pharyngeal lumen to the outside of the organism, allowing excess water taken in during feeding to be pumped out. Solid wastes and undigested food are passed through a dorsally placed anus, while nitrogenous and other soluble wastes passively diffuse across the body wall. Circulation and gas exchange occur by passive diffusion across the body wall, without any specialized organs to aid in the process. Osmoregulation is aided by one or several pairs of protonephridia, depending on the order the species belongs to, which release excess ions through excretory nephridiopores at the ventral surface of the organism, usually in the mid-body area.

Development

Embryonic cleavage is holoblastic and apparently spiral. After the formation of a coeleoblastula, gastrulation occurs, with two cells from the ventral surface moving into the blastocoel. This eventually leads to the formation of the entoderm and midgut. Additional invaginations form, connecting with the midgut, and two additional surface cells drop to the interior and contribute to the development of germ cells and gametes. Juveniles hatch from their egg capsules and show direct development, reaching sexual maturity in a few days. Gastrotrich species are eutelic, with development proceeding to a particular number of cells, with further size increases from increases in individual cell size rather than the production of new cells, although some gastrotrich species are capable of regeneration in response to damage or loss of tissue.

Reproduction

Gastrotich females are simultaneous hermaphroditic or parthenogenetic. Male reproductive systems consist of one or two testes, with associated ducts leading to a single pore on the ventral surface, a few species have paired pores. A caudal copulatory organ is present in a few species, including members of genus Macrodasys. The female portion of the reproductive system is composed of one or two ovaries, which lie directly behind the testes in hermaphroditic species. Eggs are produced and released into a uterine space that is bound by sperm ducts, and is associated with tissues that produce yolk for developing eggs (also called a vitellarium). From here, they are moved to a sac-like area, called the X-organ, which connects to the female gonopore. Reciprocal cross fertilization occurs when two gastrotrichs meet, while internal fertilization occurs after sperm are transferred to the female gonopore. Fertilized eggs are released via a rupture of the body wall.

Newly hatched juveniles already contain developing parthenogenetic eggs which, under favorable conditions, may be laid within a day of the mother’s hatching. Typically, four partheogenetic eggs will be laid over a four day period. Tachyblastic eggs begin to develop immediately and hatch within a day. Opsiblastic eggs are thick-shelled and very resistant to drying and freezing; these are produced when conditions are unfavorable, such as when they are overcrowded. After laying their parthenogenetic eggs, most gastrotrichs develop into simultaneous hermaphrodites, although some species remain parthenogenetic for their entire lives, most common in freshwater species. Fertilization is thought to be internal, as sperm are nonmotile and reciprocal cross-fertilization appears to be the most common mode.

Gastrotrichs do not exhibit any parental investment beyond the production of gametes and parthenogenetic eggs.

Gastrotrichs have very short lives of 3 to 21 days.

Behavior

Gastrotrichs move in a gliding fashion, using their ventral cilia. Species with adhesive tubes may use these in locomotion as well, moving in a leech-like way. Some species are known to swim, though most are relatively sessile, living interstitially in sediments or attached to the substrate with the aid of their adhesive tubes. Although population levels may be quite high locally, they are considered solitary animals. Their activity does not appear to be affected by the presence or absence of light.

Food Habits

Gastrotrichs generally feed by generating currents using pumping actions of their muscular pharynx or ciliary currents, which draw food particles into the mouth. The primary component of most of their diets is bacteria; they also consume algae, protozoans, detritus and inorganic particles. Some species may use a tactile chemical sense to distinguish between food types.

Predation

As very small organisms, gastrotrichs play an important part in their ecosystem’s food chain and are probably a food source to most benthic invertebrate predators. Known predators include turbellarians, heliozoan and sarcodine amoebae, cnidarians, and tanypodine midges.

Communication and Perception

A large, bi-lobed cerebral ganglion is located above the pharynx, with each lobe giving rise to a longitudinal nerve cord that extends to the posterior end of the body. The spines and bristles found around the outside of the body serve as tactile receptors, some species may have ciliated chemosensory pits on the sides of the head, or photosensitive pigment ocelli in the cerebral ganglion.

Source: The Animal Diversity Web